[Updated, April 15, 2016] The past year has broken records for warmth in the Arctic, and around the world. First, 2015 was the warmest year on record. Then January 2016 smashed global records to become the hottest January. February 2016 was the hottest February ever recorded, and the most abnormally warm month, breaking a record set just two months earlier.

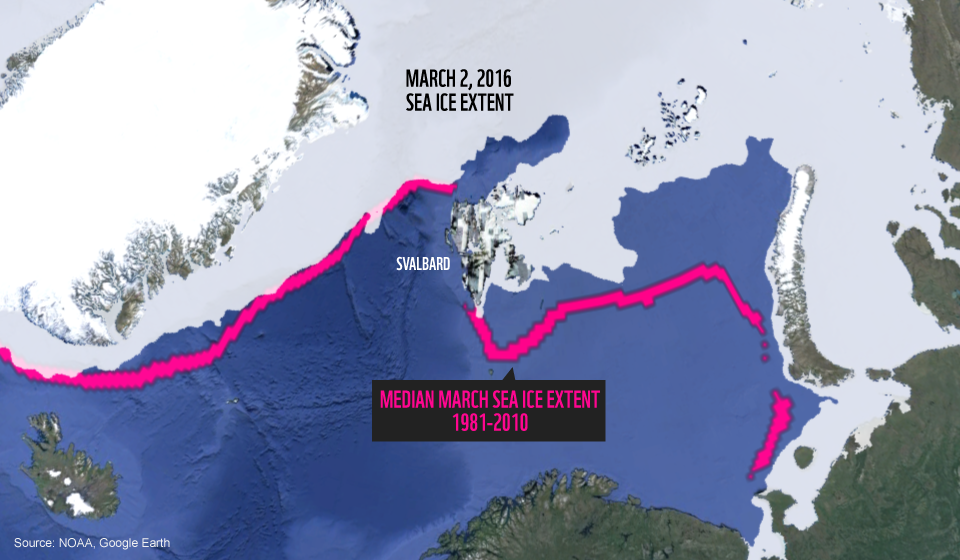

Around this time of year, sea ice in the Arctic generally reaches is maximum extent before beginning its summer melt. But not surprisingly, sea ice has also broken records. The ice hit a maximum of 14.52 million km2 on March 24. This is the lowest winter maximum ever recorded, beating the previous low maximum set last year.

Svalbard, an archipelago in Norway’s high Arctic, was one of the most anomalously hot places on earth this year. It’s also home to a large and well-researched polar bear population. Polar bears rely on sea ice to hunt for seals, their preferred prey. This year, sea ice was missing from much of the archipelago.

Since 2003, WWF has tracked Svalbard polar bears by satellite. We talked to Jon Aars, a polar bear biologist with the Norwegian Polar Institute to find out what’s happening with the bears we’re following.

Jon tells us that last summer, the bears were in good condition – there was plenty of ice, and it melted late, particularly around eastern Svalbard. This year’s low ice levels mean the bears could have much less time to hunt, making for a challenging year.

Listen: WWF’s Clive Tesar interviews Jon Aars of the Norwegian Polar Institute about this winter’s extreme melt.

North Svalbard

Two polar bears on shore in northern Svalbard. Normally, this area would be completely ice covered in March.

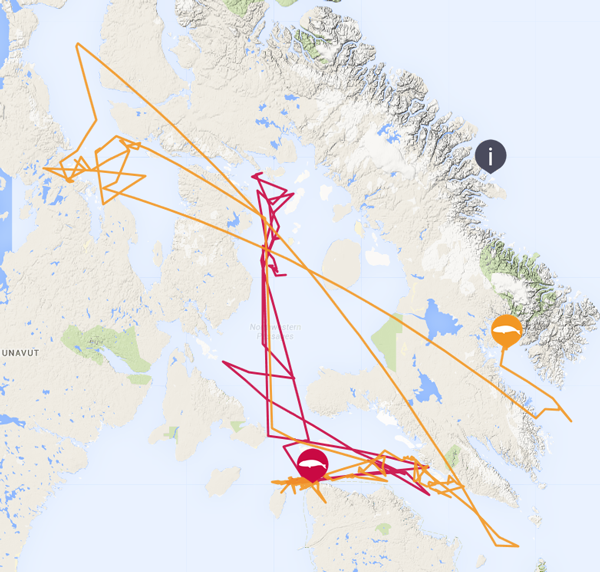

This year, we’re tracking two bears in the north. One, N26165 (blue), is currently in a den. There’s now a small amount of ice in the vicinity of her den, but it’s hard to tell how long it will stick around. Mother bears tend to be thin and hungry when they emerge from dens – giving birth and nursing cubs takes a lot of energy. They are at a disadvantage if there isn’t plenty of ice – ringed seal habitat – around when they emerge in the spring.

The other, N26243 (orange), headed up on the ice early in the season. But as the ice disappeared, she headed back to the coast. She waited around for ice before moving west.

In past years, we’ve also tracked bears who have gone far out onto the sea ice. Isdimma2’s collar stopped functioning in June 2015, so we don’t know if she managed to make it back to Svalbard this year to den or spend the winter.

West Svalbard

This mother and daughter have had very little access to sea ice this year.

A mother bear, N23979 (orange) and her adult daughter N23980 (green) have had very little access to sea ice this winter. N23980 has been seen feeding on goose eggs and harbor seals in the summer, but she would ideally have access to ice and ringed seals by now.

“In western and northern areas there is still very little ice”, says Jon, “and cold weather for the next couple of months will be important for the bears.”.