polar bear (Ursus maritimus)

narwhal (Monodon monoceros)

beluga (Delphinapterus leucas)

bowhead (Balaena mysticetus)

ringed seal (Pusa hispida),

bearded seal (Erignathus barbatus)

spotted seal (Phoca largha)

ribbon seal (Phoca fasciata)

harp seal (Pagophilus groenlandicus)

hooded seal (Cystophora cristata)

walrus (Odobenus rosmarus)

It’s looking more and more likely that sea ice in the Arctic has broken yet another ominous record – the lowest winter extent ever recorded. While low ice in the winter isn’t necessarily a harbinger of much less ice in the Arctic summer, it is a sign of increasingly thin, slow growing ice – and that’s bad news for Arctic animals.

But just how bad? A new paper published this week is the first to assess the state of the Arctic’s ice-dependent marine mammals – 11 in all. From whales to seals to polar bears, these species depend on the seasonal comings and goings of the ice edge to find food, breed and give birth. Arctic people, especially the Inuit, depend on these animals for subsistence. The well-being of these animals matters both locally and globally.

Despite their importance, there’s still a lot we don’t know about Arctic mammals. The paper, Arctic marine mammal population status, sea ice habitat loss, and conservation recommendations for the 21st century, fills in some gaps by collating everything we know about the populations of 11 different Arctic mammals over the past 35 years – a time of rapid ice loss and thinning. Some of the paper’s findings:

Head of ringed seal above the water. Blomsterhalvøya, Spitsbergen (Svalbard) arctic archipelago, Norway.

© WWF-Canon / Sindre Kinnerød

More open water in the summer

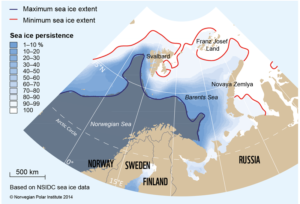

Changes in ice can disrupt life for both prey (seals give birth on ice during a short spring window) and predators (polar bears feast on the fat-rich new pups). Since the 1980s, some parts of the Arctic have seen much longer periods of open water in the summer – from 5 weeks to as much as 5 months longer.

Population trends vary, but ice is key

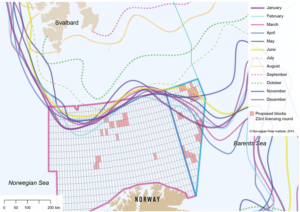

Data in the Arctic can be spotty, but the researchers founds some clear trends. In areas where ice is declining quickly, mammals that depend on ice are too. Seals and polar bears are particularly affected. Whales, meanwhile, could benefit from less ice in the short term, as open water expands their habitat and food supplies.

However, temperate species are also expanding their ranges. Killer whales, with a long dorsal fin that makes navigating in ice difficult, are moving north into previously icy waters where they prey on Arctic whales.

Ice dependent mammals, likewise, may move north when possible. Polar bears, for example, are already moving towards the Last Ice Area, a fringe along northern Canada and Greenland where ice is expected to remain the longest.

More info needed

For most of the populations reviewed, there simply isn’t much data available. “Accurate scientific data – currently lacking for many species – will be key to making informed and efficient decisions about the conservation challenges and tradeoffs in the 21st century,” says author Kristin Laidre.

Although monitoring every population fully is essentially impossible (due not least to financial constraints), the authors encourage goverments to commit to an improvment in long-term monitoring, and to look at other methods of data collection, such as working with subsistence hunters or exploring remote technologies.

What can we do?

In an environment that’s changing so quickly, conservation measures need to be fast, creative and well-balanced. The authors recommend that governments continue to work with local and indigenous peoples to co-manage Arctic mammal populations. They also suggest that management consider the responses of different species to changes in ice, and more study and mitigation of industrial impacts in Arctic water.

That means protecting the key habitats for these mammals, and avoiding risky industrial development projects in such crucial places.

WWF also recommends focusing attention on places where ice will persist the longest, like the Last Ice Area.

But ultimately, only global commitments to reduce carbon emissions can slow the loss of sea ice habitat in the Arctic. “We may introduce conservation measures or protected species legislation, but none of those things can really address the primary driver of Arctic climate change and habitat loss for these species,” says Laidre.

A global switch from fossil fuels to wind, solar and other renewable energies can help reverse ice loss in the Arctic. A WWF study found that it is not only feasible, but cost-effective, for 100% of the world’s energy to come from renewable sources by 2050.