This article originally appeared in The Circle 01.15.

Using solar energy in Northern communities is a tough sell. Just ask Klaus Dohring, president of Green Sun Rising, a Canadian company based in Windsor, Ontario that develops and supplies solar systems to generate clean electricity and heat. He says reaction to using these forms of renewable energy in the Arctic is still a mix of preconceptions, misconceptions and skepticism even though it is already meeting with success.

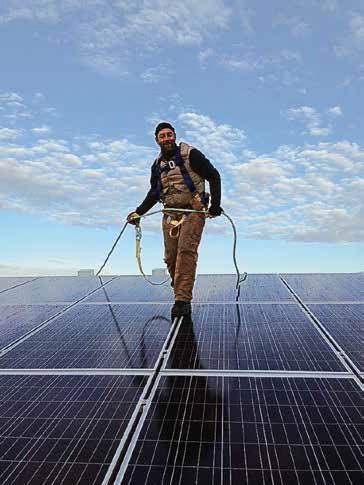

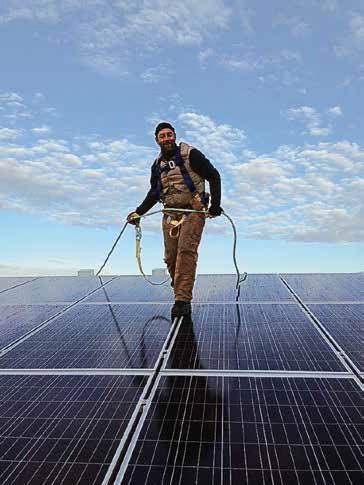

Solar energy technology being installed in Hay River, Northwest Territories, Canada. Photo: Green Sun Rising.

“Whenever I suggest using solar energy in Northern communities, the typical response is that there is too little, or no sunshine in the winter months. This is irrefutable. But so is the flip side of that argument: in the summer there is an abundance of sunshine in the far north. The city of Yellowknife in Canada’s Northwest Territories gets about 8 per cent more sun energy per year than Berlin, Germany. In its peak summer months of May and June, Inuvik—also in the Northwest Territories and located 2 degrees above the Arctic Circle—gets more sun energy per month than Rio de Janeiro in any of its best months. For a good half of the year the sun is a great energy resource for the north.

The harsh northern climate is usually cited next in the argument against solar energy in northern climes. Space is an even harsher environment than the Arctic, yet satellites and the International Space Station are great examples of solar powered systems operating well in space. The Mars rover is an electric vehicle purely solar powered, also operating under extremely harsh conditions. Solar cells actually get more efficient with lower ambient temperatures because they like being cold. With no moving parts, a solar photovoltaic system in which light (photons) are converted into electricity (volts) can hibernate through the harsh arctic winter and generate electricity as soon as the sunshine is available for the solar cells.

We have introduced both solar photovoltaic as well as solar thermal systems into Northwest Territories applications, and the systems operate well.

Solar thermal systems can be used to generate heat energy. While the system itself is different from solar photovoltaic

, the sun availability is the same. A solar thermal system allows for simple and easy generation and storage of heat energy, in the form of hot water.

One litre of diesel fuel typically provides 3 kilowatt hours (kWh) of electricity via the generator. At current economics of C$1.20 per liter plus an assumed 25 per cent transportation cost added, this results in variable cost of at least C$0.50 per kWh just for fuel cost reduction, higher for more remote communities. The full cost of diesel generated electricity is typically in the several dollars per kWh range, two-thirds of which is government-subsidized in Canada.

In the province of Ontario, the current solar incentive program puts a value of less than C$0.40 per kWh on solar generated power, and the incentive program is still considered attractive.

Against the variable cost of diesel fuel reduction, a solar system is already financially viable. When considering the true cost of diesel generation, a solar system will be a substantial cost savings. In terms of quality of life and pollution, a solar system is quiet, has no emissions, and is the most environmentally friendly way to provide energy. Once installed, the ongoing operating cost is zero.

Northern communities are accustomed to large diesel tanks with fuel delivery once per year, and using fuel from the tanks all year around. A large scale solar thermal system with big and very well insulated storage tanks allows the harvest of abundant summer solar energy which can also be stored for year round usage. Now the sun is the fuel delivery vehicle coming very reliably every summer, providing clean energy free of charge. Drake Landing Solar Community in Alberta, Canada has an operating example of such a long term storage system for solar thermal energy. There are over 100 others in operation across Europe. Conceptually, a solar thermal system with seasonal heat storage of sufficient size can meet all of the heat energy needs of a northern community.

Wind power has yet to build a track record of being able to withstand Arctic conditions, but it is starting to. For electricity, after the summer solar photovoltaic potential has been exhausted, a combination of solar system with battery storage plus wind power can provide most of the communities’ needs, with a diesel back-up system. In Antarctica, a harsher environment than the Arctic, the Princess Elisabeth Station has been operating since 2004 purely on solar and wind power.

With the onset of electric vehicles (EV) there is now significant development in battery storage systems. Utility scale battery systems are being introduced, and northern communities will be able to benefit from clean and quiet electricity storage in battery systems, which can at least bridge the daily variations of solar power, and start to reduce the seasonal impacts. The community of Colville Lake, Northwest Territories is set to receive such a utility battery system in 2015. It is expected that the combination of solar system with battery storage will greatly reduce diesel usage in summer.

Ultimately, electric vehicles will also become a preferred choice for Northern communities, once clean and renewable energy is available. We operated two electric cars through last winter, when the Arctic vortex brought Arctic winters to Ontario. Both EVs did well, with reduced range. The Arctic Energy Alliance is now starting to operate one EV in Yellowknife, and will generate real life experience with an EV under Northern conditions.”