Harbour crab, Lofoten, Norway. © Wild Wonders of Europe /Magnus Lundgren / WWF

The ocean has absorbed nearly one-third of the carbon dioxide (CO

2) added to the atmosphere by humans from deforestation and the burning of fossil fuels. Because the ocean has absorbed so much CO

2, greenhouse warming of the atmosphere is less severe. But, there is a critical downside: the dissolved CO

2 increases the acidity of ocean water, threatening aquatic life and the livelihoods that depend on it. Without global action to limit CO

2 emissions, this trend will continue.

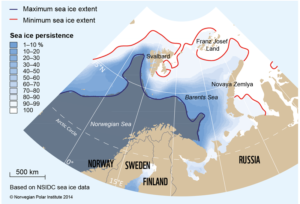

Ocean acidification is a big issue for the Arctic, where relatively shallow water depths and significantly large CO

2 influx from both human and natural sources can result in acidic waters, leading to substantial impacts on a very vulnerable food web. Exacerbating the problem is the fact that the relatively cold waters of the Arctic allow CO

2 to be absorbed more easily than in warmer tropical waters, amplifying the acidifying effect of atmospheric CO

2 at polar latitudes. In addition, as ice melts in the Arctic, the seawater becomes less salty, and less salty water absorbs CO

2 more efficiently. Yet with all of these potentially significant impacts and related consequences, acidification of the Arctic Ocean is poorly understood, under-observed and under-researched. Continued anthropogenic climate change and increasing amounts of carbon uptake by the Arctic Ocean are likely to have significant detrimental impacts on the physical, biological, social and economic state of today’s, and especially tomorrow’s, Arctic communities.

Acidification of the Arctic Ocean is poorly understood, under-observed and under-researched.

What we Already Know

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 5th Assessment Report included several important findings with relevance to both global ocean health and acidification of the Arctic Ocean, including:

- Ocean warming dominates the increase in energy stored in the climate system, accounting for more than 90% of the energy accumulated between 1971 and 2010 (60% above 700m, 30% below 700m)

- Ocean acidity has increased approximately 30 percent since the Industrial Revolution

- More acidic oceans will have broad and significant impacts on marine ecosystems, the services they provide, and the coastal economies, which depend on them

- Oceanic uptake of anthropogenic CO2 will continue under all future emission scenarios, however, uptake is greater for higher concentration pathways – causing even more acidification, with carbon cycle feedbacks that will exacerbate climate change

The U.S. Perspective

U.S. federal agencies are currently conducting research, implementing policies and developing measures to better understand and address the effects of ocean acidification. But more is needed. We believe the U.S. must continue to lead the charge for the international community to increase international collaboration on ocean acidification research in the Arctic, particularly with regard to the effects of acidification on shell-forming organisms, marine biodiversity and food security.

Ocean acidification was one of the three topics that Secretary John Kerry chose to highlight in the Our Ocean conference. The Our Ocean Action Plan, released by Secretary Kerry during the conference, identified the importance of reducing CO2 emissions to stem the increase in ocean acidification and the need to create worldwide capability to monitor ocean acidification.

The U.S. continues to promote the development and establishment of the Global Ocean Acidification Observing Network (GOA-ON), which will measure ocean acidification through the deployment of instruments in key ocean areas. This is a new network with broad international cooperation and a commitment to build capacity in developing countries. Since 2012, the United States hasprovided financial support, totaling approximately $1 million, and related in-kind support for the establishment of a new Ocean Acidification International Coordination Center (OAICC) based in Monaco, which will help facilitate global cooperation to advance our understanding of ocean acidification.

Recommendations for Action by the Arctic Council

During its 2015 to 2017 Chairmanship of the Arctic Council, the U.S. should take a leadership role in:

- Promoting the development of a full-scale, rigorous assessment of Arctic Ocean acidification by the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme’s (AMAP) Arctic Ocean Acidification Expert Group.

- Continuing to support efforts like Global Ocean Acidification Observing Network through monetary and expertise contributions.

- Developing a communications and outreach strategy aimed at raising awareness of Arctic Ocean acidification (OA) as an issue that impacts the globe- not just the Arctic

- Developing a focused mechanism for directly connecting the U.S. OA Interagency Working Group (IWG) with states, NGOs, foundations, academia, local communities and private industry – within the U.S. and across the Arctic Council countries to share best practices and lessons learned in addressing the causes of and impacts from OA.

- Developing strategies for raising the profile of OA—and Arctic Council-led solutions—in upcoming UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) COPs

- Developing strategies/efforts for raising the profile and scientific expertise capacity of OA within the more mainstream Arctic Council climate change efforts, such as AMAP’s assessments and monitoring activities.

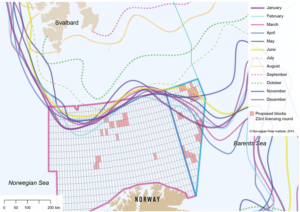

- Utilizing the circum-Arctic countries’ leadership elements within AMAP and Sustaining Arctic Ocean Observing Networks (SAON) to find creative ways to help fund standardized OA monitoring instruments across international borders and leverage existing and planned activities across borders

- Organizing a roundtable discussion with leading industry players, NGO and/or philanthropic leaders with a focus on determining the requisite science and monitoring assets needed to better understand past, present and future trends of OA as well as the resultant impacts and effects

- Proposing oil and gas companies with offshore oil platforms in the Arctic add monitoring devices to their installations