This week, Arctic governments are meeting in Norway to talk about Arctic biodiversity. But they need to do more than talk. They’ve invested in reams of excellent research on life in the Arctic – now they need to act! They’ll make commitments this April, when the United States begins its chairmanship of the Arctic Council. Will they commit to Arctic action? This week, we look at #5ArcticActions nations can take to protect Arctic life:

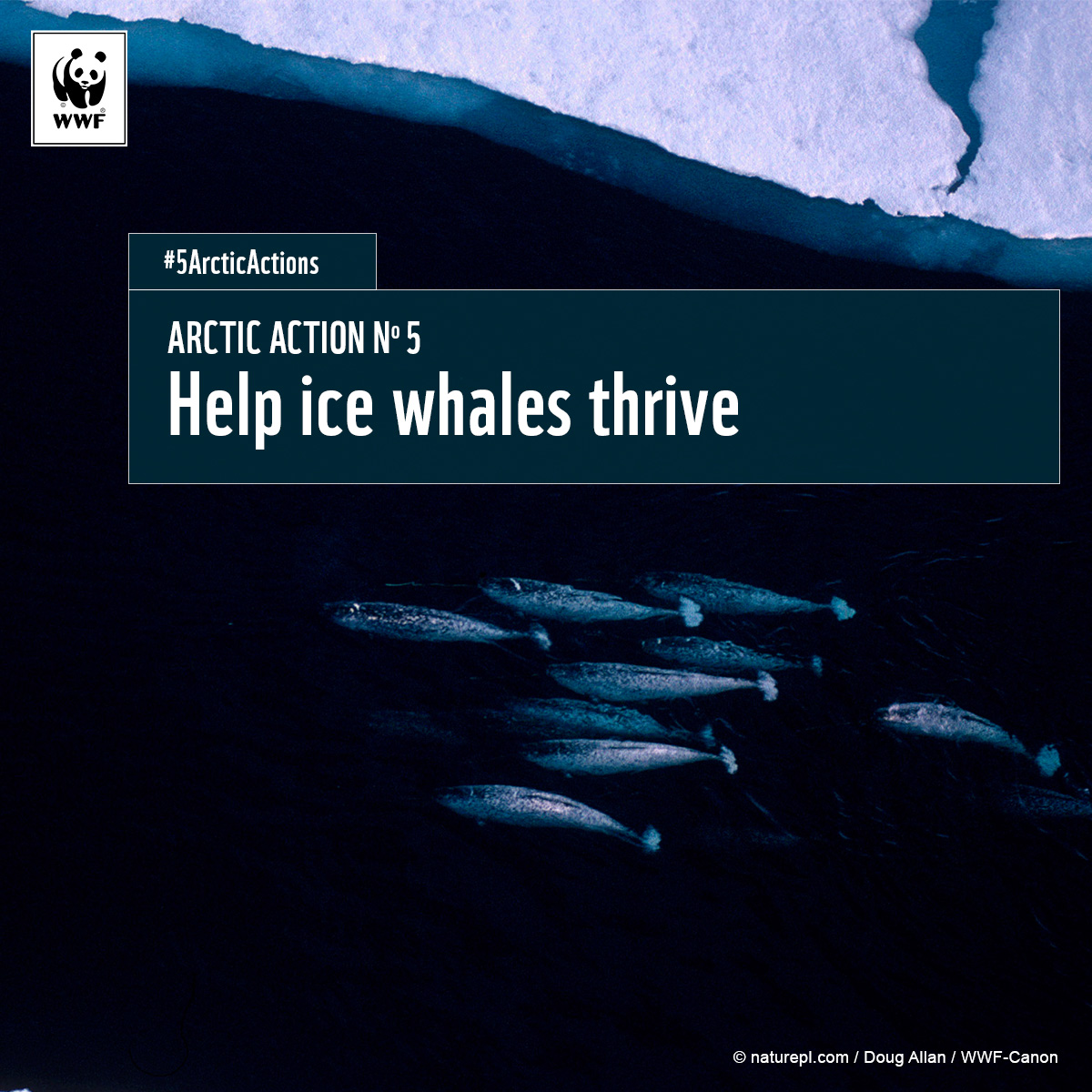

WWF’s Pete Ewins is a biologist focused on the ice whales – narwhals, belugas and bowheads.

Why are international whale conservation efforts important for Arctic life and livelihoods?

The three whale species that have evolved superbly to life in the harsh arctic marine ecosystems move over huge distances, and of course don’t recognize political boundaries. Their annual cycle and whole ecology is governed by finding sufficient food, conserving energy, and avoiding predators and mortality risks.

Inuit have evolved superbly too in the same habitats – and depend on the harvesting of energy-rich marine mammal species like these whales.

So, these whales and the places where they concentrate are critical to Inuit livelihoods and cultural and spiritual traditions. In the face of unprecedented rapid changes across the Arctic, northerners seek to continue harvesting these species sustainably – that is a very important part of who Inuit are. So, all efforts to ensure that continued harvesting of these whale populations can occur in a sustainable manner, well-managed, and with the most important habitats protected from the escalating high risks of industrial activity, are a very high priority for WWF and local people.

Why do Arctic states need to improve on their approach to whale conservation?

That is simply what responsible governance is supposed to entail – the need to translate all the facts available, including climate change projections, in the long-term best interests of people, into effective plans and well-balanced decisions. Sadly, despite the acknowledged very high risks (for example, a lack of proven techniques to recover oil spilled in iced waters), and some big information gaps, decision-makers have largely ploughed on with an old-fashioned mentality and paradigms. Boom while you can, and just deal with any problems when they occur.

That, in the view of WWF and many many local people for whom these areas are ‘home,’ is simply reckless and highly likely to push future generations into a very challenging future. This is avoidable of course – but those in elected office to up their game, based on all the facts and experience available now.

Are particular states showing leadership?

Norway established the Svalbard National Park, including huge marine areas. In Canada, the establishment of the Ninginganiq Bowhead Whale Sanctuary is a great example of an area protected because of its well-documented use at certain times of year by whales.

What concrete action can Arctic states take in the next year?

Each could refresh their commitments to establishing an adequate network of the most important habitats for the ice whales – pledging to protect an adequate network of ALL the key areas needed now by these species.

The Arctic Biodiversity Assessment made clear and strong recommendations. Now states need to implement them.

Is there anything the public can do?

So far, Arctic leadership has operated on a business-as-usual ticket. The public can pressure Arctic governments to create a satisfactory network of protected areas for wildlife (call them sanctuaries or whatever you like, but they need to be essentially exclusion zones for industrial activities).