This article originally appeared in The Circle, WWF’s quarterly Arctic journal, issue 01.16. See all articles here. Previous issues of The Circle can be downloaded here.

One issue continues to cloud the EU’s role in the Arctic. The sealskin trade issue has become emblematic of the Union’s failure to maintain the interests of Arctic peoples. Former Member of the European Parliament DIANA WALLIS reflects on the campaign that has haunted EU-Arctic relations. Wallis is the President of the European Law Institute and British former Member, then Vice-President of the European Parliament.

AS I WRITE THIS, it is the day after Christmas Day. In many rural communities in England this day is still marked by the so-called Boxing Day hunt, although the actual killing of a wild fox is now banned. I have often wondered whether, in 2008/2009 as the European Parliament’s rapportuer on the proposal for a Regulation on the Trade in Seal Products, what the feeling would have been if the EU and not our Westminster Parliament had sought to achieve legislation which limited fox hunting. Of course, those who are adamantly against fox hunting may not care who legislates, but there is a problem here and it should not be too easily dismissed. This is especially true with an entity like the EU, which is very much a legal construct only empowered by the Member States of the Union to legislate in accordance with the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality.

The main problem with the Regulation on Seal Products, from my point of view, was that it was never really clear what the European Parliament was legally trying to achieve, nor why we were doing it within a legal framework meant only to regulate the circulation of goods in the European market. It now seems clear, thanks to the outcome of lengthy proceedings in the World Trade Organization (WTO), that if Europe ans do not want seal products in their market based on cultural grounds or sensitivities, then that is their right, as long as the prohibition or exemptions to it are applied consistently.

However, the European legislative process was, at the time, less about products and much more about hunting, especially the hunting of seals in Canada. It seemed from the piles of letters that arrived in my office that a very active and competent animal rights NGO had instigated a huge campaign. Humane Society International, which has its origins in the U.S., was very successfully campaigning to get the European legislature to regulate an activity carried out in a third state: Canada. It seemed all the more strange given that there is also a large seal hunt in Namibia, but this was almost never mentioned as the concentration was on cruelty in Canada.

When I took the role as Parliament’s rapporteur I did so on the basis of a track record of activity in relation to the Internal Market and a huge interest in Arctic affairs. Indeed, with others, I had been instrumental in several resolutions of the Parliament on Arctic issues, as we then thought the EU was edging towards membership of the Arctic Council. Every time the Arctic was discussed in the Parliament there was huge emphasis on the rights of the Indigenous peoples of the Arctic. Here I thought was a chance to bring this together.

The proposed legislation purported to exempt seal products hunted by such peoples for subsistence purposes, but the fact that their products would be associated with a ‘ban’, seemed inevitably damaging to any genuine market. I started to formulate an alternative proposition based on a labelling regime, thus leaving the market and the informed consumer to decide. Even the ‘ban’ itself would require comprehensive labelling to maintain so it was not such an unworkable or burdensome alternative. To me it had the merit of offering some sort of lifeline to the fragile Indigenous communities, especially in places like Greenland. More importantly, I thought it better respected the proportionality and subsidiarity requirements that all EU law should meet.

Prior to the first vote in committee there appeared to be a broad coalition prepared to support this alternative proposition. However, animal rights activists had been busy contacting ministers in capitals and European political parties. It should also be recalled that this came in the run-up to European Parliament elections in June 2009. Every committee member had a hotel type hanger put on their door indicating the pros and cons of each side and later every parliamentarian was to receive a fluffy white toy seal bearing a label showing blood and the slogan ‘doomed to die’ even though these white seal pups had been protected by EU conservation legislation since the 1980s.

The legitimate aim of the legislation was opaque; it was constructed finally not as a ‘ban’ or ‘prohibition’ but rather as an indication as to what goods could be placed on the EU market; that was those complying with the so-called ‘Inuit exception’. Working out how that exception applies has proved difficult in the subsequent legal wrangles. Clearly the legislation was not a conservation measure; the seal populations are not under threat, indeed fishermen will tell you there are too many eating too much fish! If it was an animal welfare concern then seals as wild animals were likely to end up with similar or greater protection than any animals reared commercially in the food chain for consumption of their meat. If the issue was a cultural one, like the ban on cat and dog fur products, then again this seemed at first encounter unbalanced given that cats and dogs are family pets in Europe, seals are not. There is no doubt, as I finally remarked, that seals have good PR, against which, sadly, Indigenous peoples cannot compete.

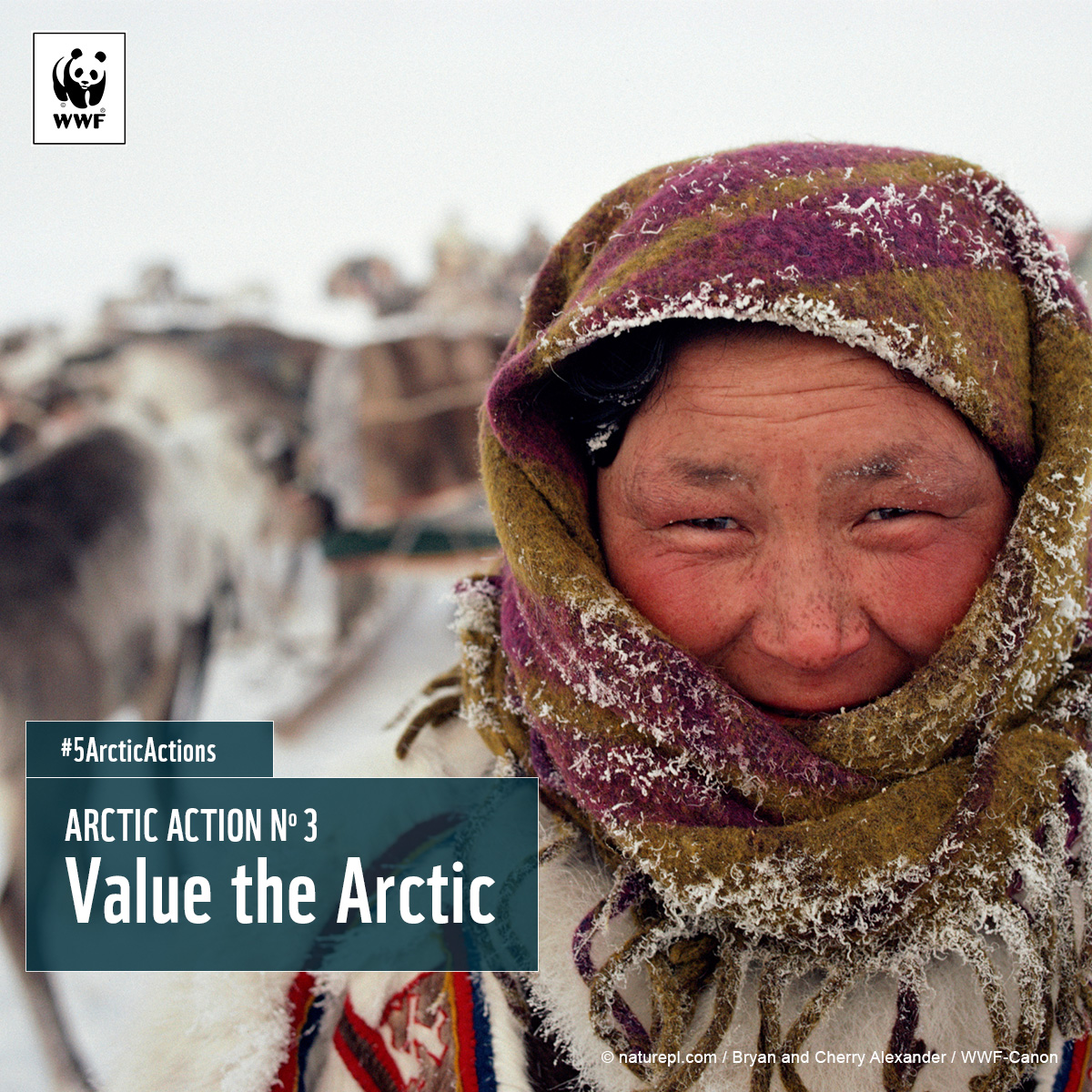

Images of Inuit women sobbing in my office, distraught at what might happen in their communities, remain with me from the process as does the shocked silence during a telephone call with a Canadian minister as she began to comprehend that a transnational legislature in another continent could intervene in the commercial activities of her country.

Aside from the damage to these Indigenous communities, there was damage to the EU’s credibility as a legitimate Arctic actor. There is little doubt in my mind that is why the EU, six years on, has not progressed to becoming an official observer of the Arctic Council let alone a full member. Of course, Canada’s new government may now take a different view.

The whole process left me wondering about EU law-making. Of course, if a measure has popular support politicians must give way, but it should be informed and legal. Also, human and animal rights should be carefully balanced. Let me put it this way, I ride horses but I would never join a hunt, nor would I want to see the EU legislating about such domestic UK matters; even more so if my country were not a member of the EU!