We’ve followed a group of satellite-tagged Bowhead whales in northern Canada for 2 years. Our Arctic whale expert, Pete Ewins, explains what the whales are up to.

File photograph of a bowhead whale. Photo: WWF/Paul Nicklen, National Geographic Stock

From the batch of Bowhead whales fitted with satellite radio tags in northern Foxe Basin in July 2013, amazingly a few of them still have working radios – coming up for nearly 2 full years of hugely valuable information on both daily positions/movements, but also details of dive times and depths! These data are crucial for informing accelerating decisions about industrial activities in these same sensitive and rapidly changing marine systems.

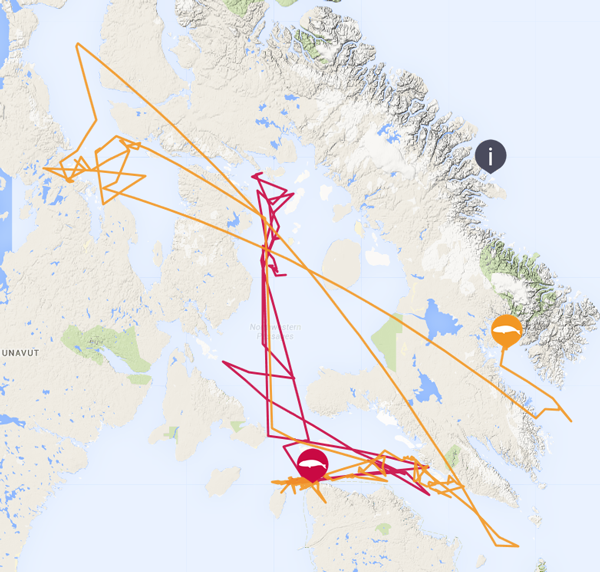

Let’s look at two individuals in particular – 128152 (Orange), and 128150 (Red).

Go to interactive map

Red and Orange spent winter of 2013-14 in Hudson Strait, and like other bowheads, generally moved from east to west over the course of the winter – associating with the predictable areas of broken ice and the relatively strong currents present there.

By late winter (March-April), it looks like the area off Digges and Mansel Islands near Ivujivik may be a very important regularly used habitat, towards the edge of the deepwater channel in central western Hudson Strait. Both of these whales headed back after May-June 2014 to Foxe Basin / the Gulf of Boothia. But Orange has wintered in 2014-15 in an entirely different area – Cumberland Sound, SE Baffin Island, moving steadily in towards the upper reaches of this huge sound by early April.

Examination of the daily sea-ice charts shows that this whale is sticking to areas of broken ice, with plenty of opportunities for breathing. It’s not thought that these whales are doing much feeding at this time of year. But the spring flush of light, energy and nutrient rich water will start soon, and these whales will capitalize for sure when they encounter large concentrations of copepods, their preferred krill-like food.

Why are these data really important for bowhead whale conservation? Well, as bowhead whale populations are still recovering slowly, but steadily, from the huge declines resulting from heavy commercial over-harvesting since the 18th century, it is important to manage all human activities that present further risks. Obviously for an ice-dependent whale like this, that means first and foremost rapid climate change and the ongoing retreat and thinning of sea-ice. March 2015 saw the record lowest cover of Arctic sea-ice since records began back in the 1970s.

All part of the projected trends, given the trends in global greenhouse gas emissions.

But on top of this major pressure, increased shipping and explorations from the oil & gas industry, presents greater and new risks of oil spills, noise disruption and displacement of marine mammals from key habitats, and of course actual ship strikes of resting whales.

This is where these data gathered from high-tech satellite tags comes in – they can be hugely important in confirming the main areas used by these sensitive marine mammals at different times of year. And then industrial projects can plan to avoid and minimize their impact on such important wildlife resources.

WWF is working hard with as many parties as possible to help plan for a healthy low-risk future, that can balance the needs of key wildlife species with the needs of local communities and a healthy economy. But in these circumstances, this means taking new approaches. That is what we continue to help develop.