This template is built on Bootstrap and is meant to work as a one-pager where you can add different types of elements, through containers. Continue reading

All posts by user

Earth Hour 2015 WordPress theme

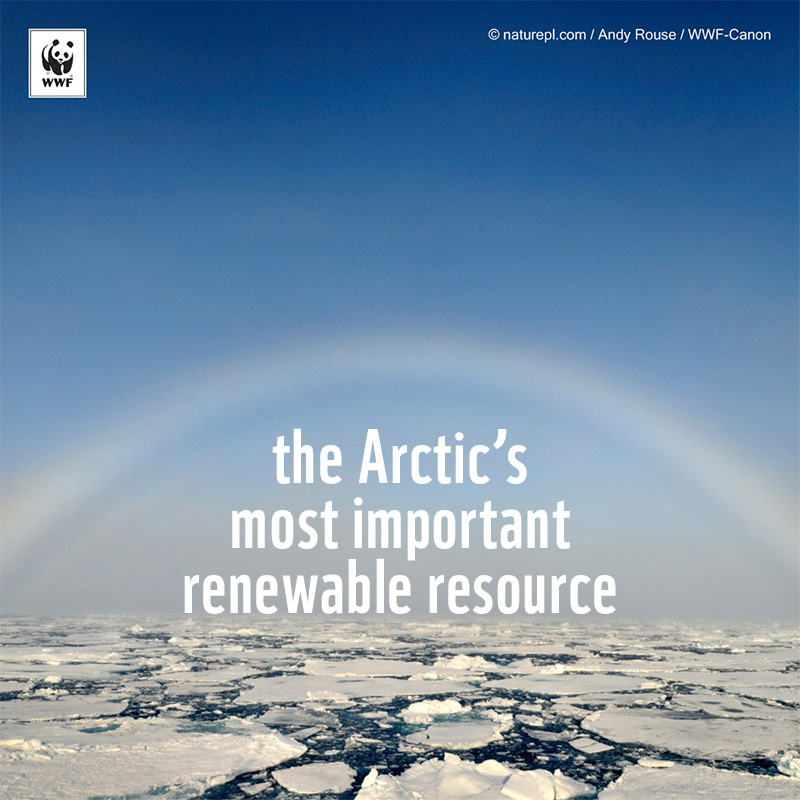

The real value of Arctic resources

WWF-Norway’s Nina Jensen speaks this week at the 2015 Arctic Frontiers conference about the future of energy in the Arctic.

As the annual Arctic Frontiers meeting starts in Tromso, Norway, much of the talk and media coverage will once again be centred on Arctic resources. This is usually code for oil and gas development in the Arctic, and the potential geopolitical conflict over the exploitation of these resources. This focus is entirely misguided.

The Arctic’s most significant renewable resources are ice and snow. The ice and snow in the Arctic reflect significant amounts of the sun’s energy. As we lose that reflective shield, the Arctic absorbs more solar energy. A warming Arctic warms the entire planet, causing billions of dollars’ worth of avoidable damage, displacing millions of people, and throwing natural systems into disarray. We continually undervalue the critical role of the Arctic is shielding us from wrenching change. Instead, we ironically look to it as a source of the very hydrocarbons that are melting away the Arctic shield.

Arctic oil and gas is risky business

Apart from the question of whether we should be developing hydrocarbon resources anywhere in the world, let us look at the question of specifically developing them in the Arctic, which in many cases means the offshore Arctic, under the ocean.

We know there are no proven effective methods of cleaning up oil spills in ice, especially in mobile ice. Even without ice, the effects of a spill in Arctic conditions will linger for decades. Oil from the Exxon Valdez spill in Alaska still pollutes beaches, more than 25 years later. We know that drilling for oil in the offshore Arctic is extremely risky – just look at the mishaps that Shell has encountered in the last couple of years in its attempts to drill off the Alaskan Coast. So there is a high risk of mishap, and no proven effective method of cleaning up after such a mishap. No matter what the price of oil, $50 or $200 a barrel, is it worth the risk?

The Arctic can be a proving ground for green technology

We do not need to make the same mistakes in the Arctic as we have made elsewhere. We can instead use the Arctic as a proving ground for greener, cleaner technologies. Tidal power, wind power, hydro power, all have potential in the Arctic. The Arctic, with its smaller population centres is ideal for smaller scale technologies to produce such renewable power. Such local power generation can create local jobs, and make Arctic communities more self-sufficient, able to withstand the fluctuations in price of petroleum-based fuels that will eventually bankrupt them.

This message is not just coming from WWF. If you look at the US government plans for its chair of the Arctic Council starting later this year, it also recognizes the value of replacing fossil fuels with community-based renewable power sources – it also just put the valuable fishery of Bristol Bay off limits to oil and gas development. So it’s not just NGOs and Arctic peoples who are questioning the value of fossil fuels in the Arctic, versus the real value of the Arctic to the world – as a regulator of our global climate.

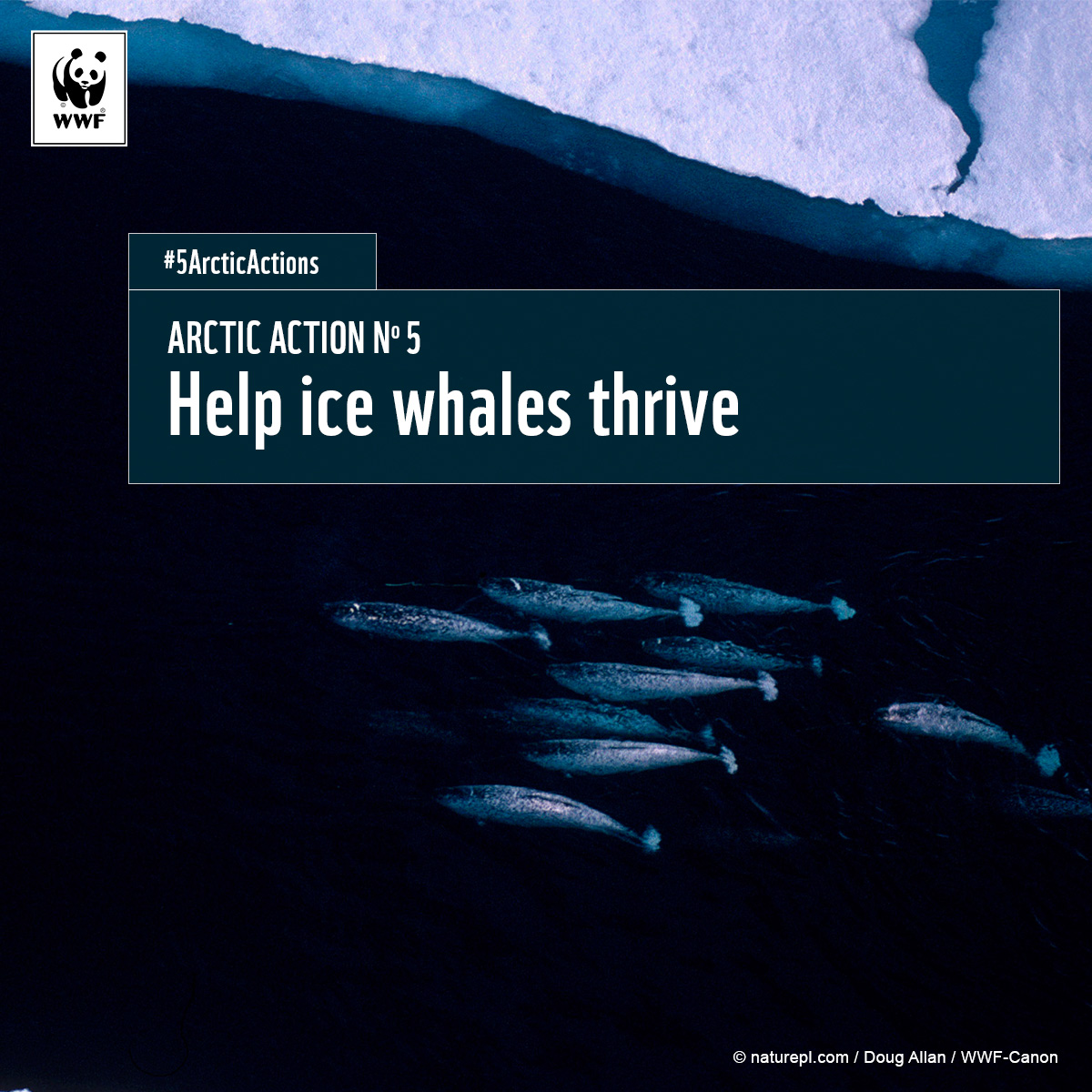

#5ArcticActions: Help ice whales thrive

This week, Arctic governments are meeting in Norway to talk about Arctic biodiversity. But they need to do more than talk. They’ve invested in reams of excellent research on life in the Arctic – now they need to act! They’ll make commitments this April, when the United States begins its chairmanship of the Arctic Council. Will they commit to Arctic action? This week, we look at #5ArcticActions nations can take to protect Arctic life:

WWF’s Pete Ewins is a biologist focused on the ice whales – narwhals, belugas and bowheads.

Why are international whale conservation efforts important for Arctic life and livelihoods?

The three whale species that have evolved superbly to life in the harsh arctic marine ecosystems move over huge distances, and of course don’t recognize political boundaries. Their annual cycle and whole ecology is governed by finding sufficient food, conserving energy, and avoiding predators and mortality risks.

Inuit have evolved superbly too in the same habitats – and depend on the harvesting of energy-rich marine mammal species like these whales.

So, these whales and the places where they concentrate are critical to Inuit livelihoods and cultural and spiritual traditions. In the face of unprecedented rapid changes across the Arctic, northerners seek to continue harvesting these species sustainably – that is a very important part of who Inuit are. So, all efforts to ensure that continued harvesting of these whale populations can occur in a sustainable manner, well-managed, and with the most important habitats protected from the escalating high risks of industrial activity, are a very high priority for WWF and local people.

Why do Arctic states need to improve on their approach to whale conservation?

That is simply what responsible governance is supposed to entail – the need to translate all the facts available, including climate change projections, in the long-term best interests of people, into effective plans and well-balanced decisions. Sadly, despite the acknowledged very high risks (for example, a lack of proven techniques to recover oil spilled in iced waters), and some big information gaps, decision-makers have largely ploughed on with an old-fashioned mentality and paradigms. Boom while you can, and just deal with any problems when they occur.

That, in the view of WWF and many many local people for whom these areas are ‘home,’ is simply reckless and highly likely to push future generations into a very challenging future. This is avoidable of course – but those in elected office to up their game, based on all the facts and experience available now.

Are particular states showing leadership?

Norway established the Svalbard National Park, including huge marine areas. In Canada, the establishment of the Ninginganiq Bowhead Whale Sanctuary is a great example of an area protected because of its well-documented use at certain times of year by whales.

What concrete action can Arctic states take in the next year?

Each could refresh their commitments to establishing an adequate network of the most important habitats for the ice whales – pledging to protect an adequate network of ALL the key areas needed now by these species.

The Arctic Biodiversity Assessment made clear and strong recommendations. Now states need to implement them.

Is there anything the public can do?

So far, Arctic leadership has operated on a business-as-usual ticket. The public can pressure Arctic governments to create a satisfactory network of protected areas for wildlife (call them sanctuaries or whatever you like, but they need to be essentially exclusion zones for industrial activities).

#5ArcticActions – Help people and polar bears coexist safely

This week, Arctic governments are meeting in Norway to talk about Arctic biodiversity. But they need to do more than talk. They’ve invested in reams of excellent research on life in the Arctic – now they need to act! They’ll make commitments this April, when the United States begins its chairmanship of the Arctic Council. Will they commit to Arctic action? This week, we look at #5ArcticActions nations can take to protect Arctic life:

WWF’s Femke Koopmans is a specialist in human/polar bear conflict.

On December 4, 2013, representatives of all five polar bear range states pledged to take major steps to safeguard polar bears. Their declaration at the International Polar Bear Forum included a promise to reduce conflict between people and polar bears. A year later, there’s still a great deal of work to be done.

Why do we need to address conflict between people and polar bears now?

Human-polar bear conflicts is increasing in many parts of the Arctic as the bears lose their sea ice habitat. It’s not just a conservation concern (that is, bears getting killed in conflict), but also a social issue. People living and working in the Arctic share their communities with polar bears, which means that they risk losing sled dogs or stored food, getting injured or even being killed when interacting with bears. It is very important to prevent this from happening and to provide them with resources to interact with bears safely.

Why do Arctic states need to improve on conflict issues?

The Arctic states are responsible for what happens in their Arctic backyard. This includes the safety of its inhabitants; both people and wildlife. There are initiatives at local and international scale to prevent human-polar bear conflicts, but strong support at the national level is needed to support local conflict projects, and to share knowledge between communities. Countries should also ensure that international strategies on human-polar bear conflict are implemented on the national level.

How one community in Russia’s Arctic is keeping bears and people safe

What action can Arctic states take in the next year?

If there’s no national strategy to reduce human/polar bear conflict, develop one – and ensure there’s sufficient funding.

Arctic states can also get better at sharing information on conflict with each other. There’s a new database of polar bear /human interaction – the more data countries can draw from, the better they can prevent and mitigate conflict. Countries should commit to adding their conflict information to the database.

Is there anything the public can do?

If you’re visiting the Arctic, learn about polar bear behaviour and how to prevent conflict.

If you’re outside the Arctic, support a move to renewable energy. Human-polar bear conflict is one of the many results of climate change. Changes in sea ice mean polar bears spend more on shore – and interact with people more often.

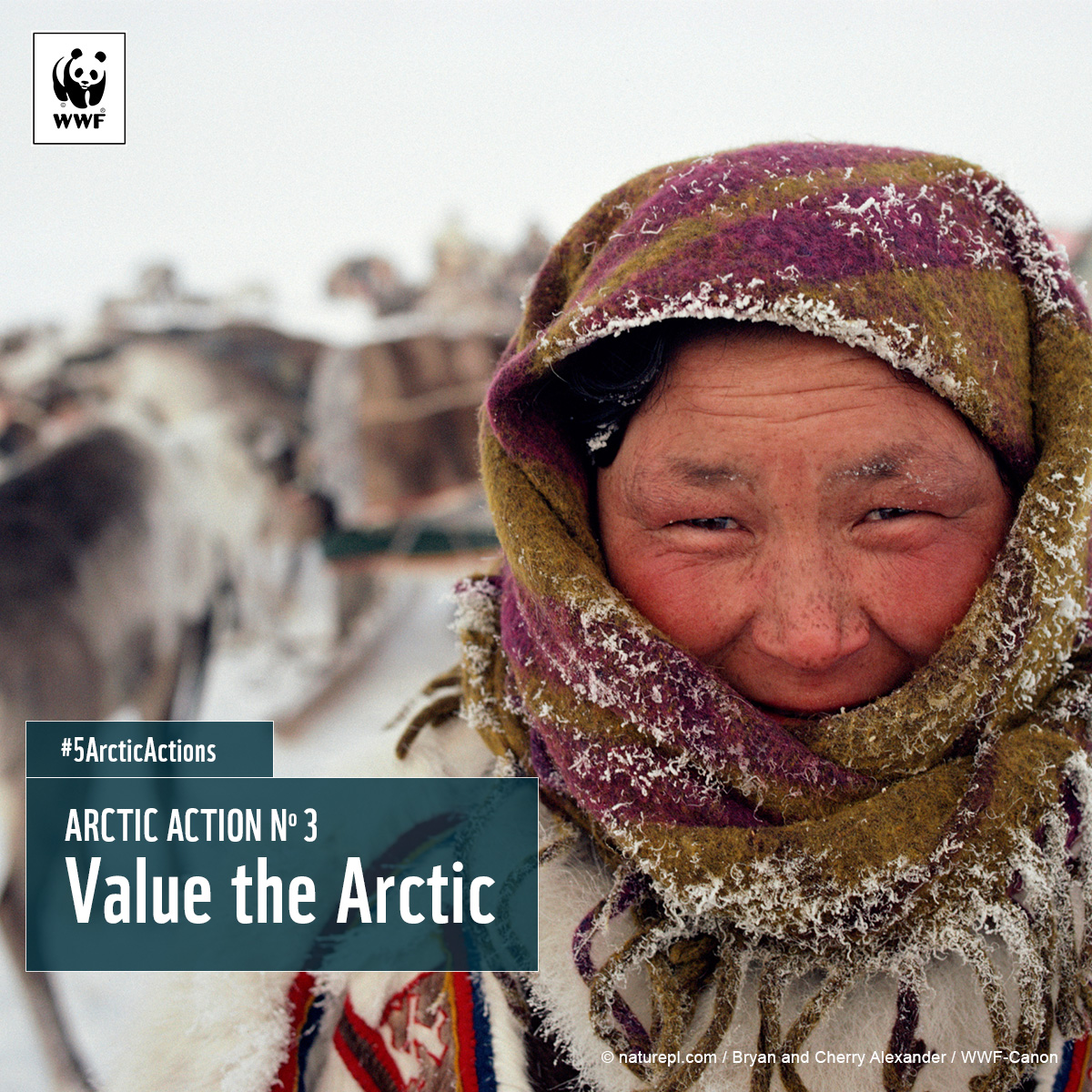

#5ArcticActions – Recognize the value of the Arctic

This week, Arctic governments are meeting in Norway to talk about Arctic biodiversity. But they need to do more than talk. They’ve invested in reams of excellent research on life in the Arctic – now they need to act! They’ll make commitments this April, when the United States begins its chairmanship of the Arctic Council. Will they commit to Arctic action? This week, we look at #5ArcticActions nations can take to protect Arctic life:

WWF’s Martin Sommerkorn is part of an international partnership looking at how people, governments and businesses value the Arctic.

Why is this work important for Arctic life and livelihoods?

The value of the Arctic can’t be measured in money alone. A place with special cultural significance has value, as do healthy caribou herds that feed communities. When governments and communities make conservation decisions, they should be taking into account everything that makes a place important.

Right now, an international partnership is asking local people, business people, researchers, economists and politicians what they value about the Arctic. Their responses will be vital guides for policy in the region.

What’s one action that Arctic states can take in the next year?

This May, the members of the Arctic Council will decide whether to take a more in-depth look at Arctic values. We want to see each Arctic country conduct a national study, and begin integrating the findings into Arctic policy. The Arctic is warming quickly – states must act now, before they lose what’s important.

Is there anything the public can do?

Learn more about the project, called TEEB for the Arctic, here.

#5ArcticActions: Work together to reduce oil risk

This week, Arctic governments are meeting in Norway to talk about Arctic biodiversity. But they need to do more than talk. They’ve invested in reams of excellent research on life in the Arctic – now they need to act! They’ll make commitments this April, when the United States begins its chairmanship of the Arctic Council. Will they commit to Arctic action? This week, we look at #5ArcticActions nations can take to protect Arctic life:

WWF’s Dan Slavik is working with communities across northern Canada on conservation issues big and small. Few issues are as big as a potential oil spill. According to new oil spill dispersion mapping, a spill in Canada’s Beaufort Sea could spread as far as Russia. And currently, there’s no proven technology to clean up a spill in icy waters.

Why is oil spill modelling important for Arctic life and livelihoods?

With the real potential for increased shipping and Oil and Gas exploration in the Beaufort Sea, there is an ever present risk of an oil spill. One Inuvialuit elder commented at the Berger Inquiry in the 1980s:

“An oil spill out there in that moving ice where they can’t control it, that’s the end of the seals. I think that not only will this part of the world suffer if the ocean is finished, I think every [Eskimo, from Alaska] all the way to the Eastern Arctic is going to suffer because that oil … is going to finish the fish. And those fish don’t just stay here, they go all over. Same with the seals, same with the polar bears, they go all over the place, and if they come here and get soaked with oil… they’re finished.”

By completing this scientific work, we hope to inform Northerners about the risk of oil spills –both big and small- and better understand how far the oil will spread, and how would it impact the communities, environment, and species of the Beaufort Sea.

Are particular Arctic States showing leadership in assessing the risk of Arctic oil/gas? How?

Environment Canada has done some good work mapping shoreline sensitivity in the Beaufort, and completing some baseline scientific research through the Beaufort Regional Environmental Assessment. However, we don’t have the capacity to effectively respond to oil spills in the Canadian Beaufort.

What’s one concrete action that Arctic states can take in the next year?

Since we can’t effectively clean up a spill, we need to ensure that–at minimum–we protect the most valuable places. Places with important cultural, biological and economic value should agreed upon by communities, nations and industry. Then, states must put in place special measures to prevent a spill (like special zoning, shipping lanes, or even no-go zones), and infrastructure to respond to a spill if it happens. This means cooperating across national borders – oil spill don’t respect boundaries.

Is there anything the public can do?

Visit http://arcticspills.wwf.ca for to explore the risks of an oil spill in the Beaufort Sea.

#5ArcticActions: Protect the Arctic’s Last Ice

This week, Arctic governments are meeting in Norway to talk about Arctic biodiversity. But they need to do more than talk. They’ve invested in reams of excellent research on life in the Arctic – now they need to act! They’ll make commitments this April, when the United States begins its chairmanship of the Arctic Council. Will they commit to Arctic action? This week, we look at #5ArcticActions nations can take to protect Arctic life:

Sea ice is the foundation of Arctic marine life. WWF’s Mette Frost is working to shape the future of a region where Arctic sea ice is likely to persist the longest – the Last Ice Area.

What is the Last Ice Area, and why is it important for Arctic life and livelihoods?

As the climate warms, Arctic sea ice is disappearing.

Almost every summer, the amount of remaining sea ice gets smaller. That summer sea ice is vitally important to a whole range of animals from tiny shrimp to vast bowhead whales, and to local people. One stretch of sea ice, along the northern coasts of Canada and Greenland, is projected to remain when all other large areas of summer sea ice are gone. This is the Last Ice Area.

WWF is supporting research on this vital Arctic habitat so Arctic people and governments can ensure life on the sea ice continues long into the future.

What can Greenland and Canada do in the next year?

We’d like to see them develop plans to establish a UNESCO World Heritage Site connecting Quttinirpaaq National Park in Nunavut with the National Park of North and East Greenland.

Are there lessons here for other Arctic states?

Unlike many of the ecosystems we work in, the Arctic is still relatively undeveloped. However, a warming climate means it’s opening up to industry very quickly. Arctic states have an opportunity to make smart conservation decisions now, before development happens, focusing on the areas that will be most resilient to climate change.

What can the public do?

- Learn more about the Last Ice Area

- Share this page

- Support conservation work in the Last Ice Area through Arctic Home

- Ask your politicians what their plans are to protect an area of remaining summer sea ice.

Protecting areas beyond national jurisdiction

This article is reprinted from The Circle 4.14. Kamrul Hossain is a Senior Research Scientist, Northern Institute for Environmental and Minority Law Arctic Centre, University of Lapland

The Arctic is dominated by a marine area that is equal in size to continental Africa and is surrounded by the landmass of six countries. The primary international legal framework applicable to the Arctic is the United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), although it has not been ratified by the United States. The high seas and the ocean floor beyond continental shelves together form what is defined in the Convention as Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (ABNJs). The states party to the Convention enjoy a set of rights in such areas, including exploitation of marine resources. They also have an obligation to conserve marine biodiversity. However, this obligation is general in nature and not underpinned by any clear protection mechanism.

Given the sensitive and fragile nature of the Arctic ecosystem, the Arctic Ocean can be regarded as an ecologically and biologically significant area (EBSA), which requires a special protection regime.

The Arctic Ocean faces numerous changes and challenges. The consequences of climate change, rapidly melting sea ice, the emergence of new shipping routes, increased access to extractive resources and other possible commercial uses of the Arctic marine environment pose alarming risks, the likely effect of which will be destruction of the marine ecological balance. Given the sensitive and fragile nature of the Arctic ecosystem, the Arctic Ocean can be regarded as an ecologically and biologically significant area (EBSA), which requires a special protection regime. Even though the concept of EBSAs is endorsed within the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) regime, it has yet to offer any concrete tool for the conservation of marine biodiversity. The CBD nevertheless endorses the concept of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), one of the objectives of which is to protect marine biodiversity. Consequently, the UNCLOS obligations concerning the preservation of marine biodiversity are complemented by the CBD. While it has been argued that UNCLOS provides a legal basis for the creation of MPAs under the general obligation set forth in article 192 in combination with article 194(5), it is not unequivocally clear whether MPAs can be established in an area beyond national jurisdiction. The general view is that an MPA can be established within an Exclusive Economic Zone, over which the coastal state has the authority to extend national regulations.

However, the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity has addressed the issue of MPAs in an ABNJ on a number of occasions. At the present, setting up MPAs in an ABNJ has taken place under the auspices of the regional sea organisations. Unlike some other sea areas, the Arctic Ocean does not have any such body – despite the coastal states’ on-going process of cohesion since the 2008 Ilulissat meeting. The Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic has established a regional sea organisation that covers part of the Arctic Ocean. The Convention provides a comprehensive legal framework for implementation of Part XII (Marine Environmental Protection) of the UNCLOS in line with the objective of the CBD, which covers a sizeable area beyond national jurisdiction. While Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMO) play an important role in the conservation of fish stocks, the Arctic Ocean is, again, only partly covered – by the North East Atlantic Fisheries Commission. There is no Arctic-wide organization.

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) has established special protective measures in defined areas – both within and beyond areas of national jurisdiction – where shipping presents a risk of impacts on marine biodiversity. The International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, adopted under the auspices of the IMO, designates Special Areas, in which maritime activities are closely regulated. The process of designating a Special Area has been further supplemented by the guiding concept of Particularly Sensitive Sea Areas (PSSA), areas requiring special protection because of recognised ecological, socioeconomic or scientific attributes that may be vulnerable to damage by international shipping activities. Whereas to date the IMO has not designated any PSSAs in an ABNJ, the ecological and biological importance of the central Arctic Ocean make it particularly sensitive as a site of marine biodiversity. The International Whaling Commission, an international body set up by the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling, has established whale sanctuaries in which whaling is strictly prohibited. These may in principle be set up in the Arctic Ocean. Nevertheless, neither PSSAs nor whale sanctuaries constitute MPAs, as they would not comprehensively regulate human activities that potentially interfere with the marine environment.

The principal legal actor in the Arctic is the Arctic Council, an organisation whose membership includes all eight Arctic states. Under the Council’s auspices and through the contribution of its working groups, the states have adopted a number of instruments relevant to the protection of marine biodiversity. While such instruments are typically not legally binding, today the Council serves as the venue to negotiate binding agreement. One record that merits mention is the 2013 Agreement on Cooperation on Marine Oil Pollution Preparedness and Response, which seeks to minimise risks from oil pollution at sea. Among the Council’s other contributions, two working groups – the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF) and the Sustainable Development Working Group (SDWG) – have recently produced the Arctic Biodiversity Assessment report and the Best Practices in Ecosystems-Based Ocean Management report, both of which are useful for fisheries conservation and management, among other purposes. Two other working groups – the Protection of Arctic Marine Environment (PAME), the Emergency Preparedness, Prevention and Response (EPPR), the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP) – together with CAFF, played a significant part in the states adopting the Arctic Offshore Oil and Gas Guidelines with a view to protecting the Arctic marine environment from unwanted environmental effects caused by offshore oil and gas activities.

The protection regime for Arctic marine biodiversity entails certain legal limitations. The designation of EBSAs does not yet have any concrete legal basis and the concept of a PSSA developed by the IMO is not a legally binding principle. Moreover, despite the fact that the UN Fish Stock Agreement is applicable to the Arctic Ocean, its scope is limited to highly migratory and straddling fish stocks; in addition, the lack of an Arctic-wide RFMO limits the protection of fish stocks occurring in the high seas. What is more, the absence of any defined legal framework for RFMOs makes it impossible to adopt concrete conservation measures, such as the establishment of Marine Protected Areas. The Arctic Council, despite its valuable contribution in producing assessment reports, has not to date focused on the conservation and management of targeted species as living resources. It does not have any working group, for example, on fisheries issues and, significantly, it may only set non-binding obligations.

Overall, the Arctic Ocean lacks a clear legal framework for comprehensive regulation of human activities that may compromise marine biodiversity in an Area Beyond National Jurisdiction. While a network of MPAs in the ABNJs of the Arctic Ocean could be an appropriate legal tool, the pertinent problem is the likely tension with regard to the rights and interests of the third states—those states that are not parties to the respective MPAs but have other rights granted under the Law of the Sea Convention within the MPAs.

Therefore, it is important to have consensus-based, multi-purpose MPAs that include actors from both inside and outside the Arctic who cooperate in negotiating comprehensive legal arrangements. The Arctic Council could take the lead here, given recent developments, such as the UN General Assembly’s initiative for a legal framework for sustainable use of marine biodiversity beyond areas of national jurisdiction. The UN proposal covers various aspects of marine biodiversity management in what has been termed the package approach.

Protecting “the great upwelling”

This article is reprinted from The Circle 4.14. Parnuna Egede is the Advisor on Environmental Issues for the Inuit Circumpolar Council- Greenland.

The North Water polynya in Baffin Bay is a huge stretch of open water surrounded by ice between Canada and Greenland. This key wintering area attracts abundant numbers of marine mammals such as polar bears and narwhals and numerous seabirds. The mixing of water currents originating from the Atlantic and Pacific causes the upwelling of nutrients to the surface. This triggers plankton blooms, which in turn boost the rest of the food web. Inuit communities are calling for a commission to consult on the protection and future use of this extraordinarily productive polynya.

What makes this polynya one of the most biologically productive in the Arctic is the formation of an ice bridge in Kane Basin north of the polynya. It blocks the otherwise constant flow of sea ice from the Arctic Ocean. When the ice bridge is absent, productivity is much lower. But formation of this ice bridge occurs less frequently now due to climate change.

The ice bridge is not only important biologically, but also historically. It served as an actual bridge for the earliest immigration and settlement of human populations from North America to Greenland beginning in 2500 B.C. up until the middle of the 20th century. This rich biological habitat still sustains Inuit communities on both sides of the bay. It is no coincidence that the Greenlandic name for the North Water polynya is Pikialasorsuaq – “the great upwelling”.

Bridging the Bay

Acknowledgement of the critical importance of Pikialasorsuaq to the Inuit was the impetus for a workshop organized by the Inuit Circumpolar Council – Greenland and co-sponsored by Oceans North Canada on “Pikialasorsuaq – Bridging the Bay” in Nuuk in September, 2013. Over twenty participants attended the two-day workshop.

Inuit hunters and fishermen from communities surrounding the North Water polynya—Pond Inlet, Grise Fiord and Arctic Bay in Nunavut, and Kullorsuaq and Qaanaaq in Greenland—shared their observations on changes in sea ice and snow conditions as well as distribution and behaviour of marine mammals. Scientists from both countries also presented their current understanding of the geology, oceanography, biology and history of this region.

This dialogue served as a basis for the discussion on potential uses and non-uses of the polynya. For example, KNAPK, The Organization of Fishermen and Hunters in Greenland advise halting seismic activities and hydrocarbon exploration offshore of Northwest Greenland. They are concerned about potential harmful effects of these activities on fishing and hunting as well as the environment, and the lack of proper compensation to fishermen and hunters for adverse effects.

The workshop succeeded in “bridging the bay”, creating a strong consensus to explore joint strategies for safeguarding and monitoring the health of this region for future generations. One significant outcome was agreement to work towards creating a joint commission mandated to consult with local communities about the future use and protection of the area.

The ice bridge is not only important biologically, but also historically. It served as an actual bridge for the earliest immigration and settlement of human populations.

Shortcomings of the international process

The input gained from the Pikialasorsuaq workshop was then shared by ICC-Greenland at the Arctic regional workshop to facilitate the description of Ecologically or Biologically Significant Areas (EBSA). This workshop was organized by the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in Helsinki in March, 2014. ICC-Greenland was invited in its capacity as a Permanent Participant of the Arctic Council.

Supported by social and cultural criteria, ICC-Greenland submitted the North Water polynya as a cross-border area fulfilling the criteria of an EBSA. But despite the fact that participating Canadian and Greenlandic/Danish scientists agreed to the importance of the polynya, it was not possible to include it as an EBSA at this level.

The reason seemed to be political reluctance to submit an area that spans national Economic Exclusive Zones for consideration. Since the EBSA process is a national process, it became evident that it falls short when it comes to:

- scientific coordination between states when EBSA are cross-border in nature

- incorporation of input from cross-border Indigenous Peoples’ Organizations

- social and cultural criteria, including significance for Indigenous Peoples

Added value of a commission

In the international process only states can put options on the table and take decisions. ICC-Greenland could only have its submission included in the report as an example of challenges to incorporate indigenous input in the EBSA process. To acknowledge the importance of the North Water polynya in the CBD, Canada and Greenland will have to submit their halves of the polynya into the CBD repository – And hope that the two pieces of the puzzle fits together.

ICC-Greenland believes that a joint commission between Canada and Greenland is the best way to ensure full and active participation of Inuit on both sides of the North Water polynya. The collective input from Inuit will add value along with scientific coordination when working towards gaining EBSA status to the polynya. This will help any conservation efforts strike a proper balance between the socially and culturally important subsistence hunting and the need to protect the habitat for generations to come.