Permanent Participants on the Arctic Council highlight what they’d like to see during the US chairmanship beginning in April 2015. This article originally appeared in The Circle 01.15.

Aleut International Association

As the representative of an island region, the Aleut International Association would like to see a focus on protection of the marine environment during the next term of the Arctic Council. This would be a continuation of work by the Arctic Council, particularly in the recent past with the agreement on marine oil pollution preparedness and response, and the arrangement on marine oil pollution prevention worked on during the Canadian Chairmanship.

In particular we hope that there will be an emphasis on safe shipping, perhaps with measures that will take the provisions of the International Marine Organization’s (IMO) Polar Code a step further. In addition, we hope that the U.S. Chairmanship will continue to expand efforts to better include Traditional Knowledge in the work of the Arctic Council, as well as examine ways to better support the Permanent Participants to engage more fully.

We hope that the U.S. will encourage further steps to mitigate the effects of climate change, but also examine ways Arctic Communities can adapt to the changes that will likely happen regardless of mitigation efforts. We also hope to see a focus on living conditions for the Indigenous peoples of the Arctic which could build on ongoing work on issues such as mental wellness, suicide prevention, language retention, and food security.

We would also like to see an initiative that examines energy in the Arctic, and looks at innovative ways to bring down the cost and environmental effects of heating and power generation with a focus on both improving existing technologies, but also an examination of new technologies such as renewables. Finally, we hope to see a renewed focus on outreach, to get the word out about the work of the Arctic Council, and the changes that are affecting the Arctic, to the global audience.

James Gamble is the Executive Director of the Aleut International Association.

The Arctic Athabaskan Council

Cooperation, climate change, cutting through geopolitics key to upcoming term

The United States assumes the Chair of the Arctic Council at a time when relations between Russia and the other circumpolar states has deteriorated due to Russia’s annexation of Crimea and support of rebels in eastern Ukraine. Some have accused President Putin of seeking to expand Russia to something like the old frontiers of the Soviet Union with the intent of increasing Russia’s influence globally. What might this mean for co-operation in the circumpolar world? Russia’s geography—eleven time zones—make it indispensable to circumpolar collaboration.

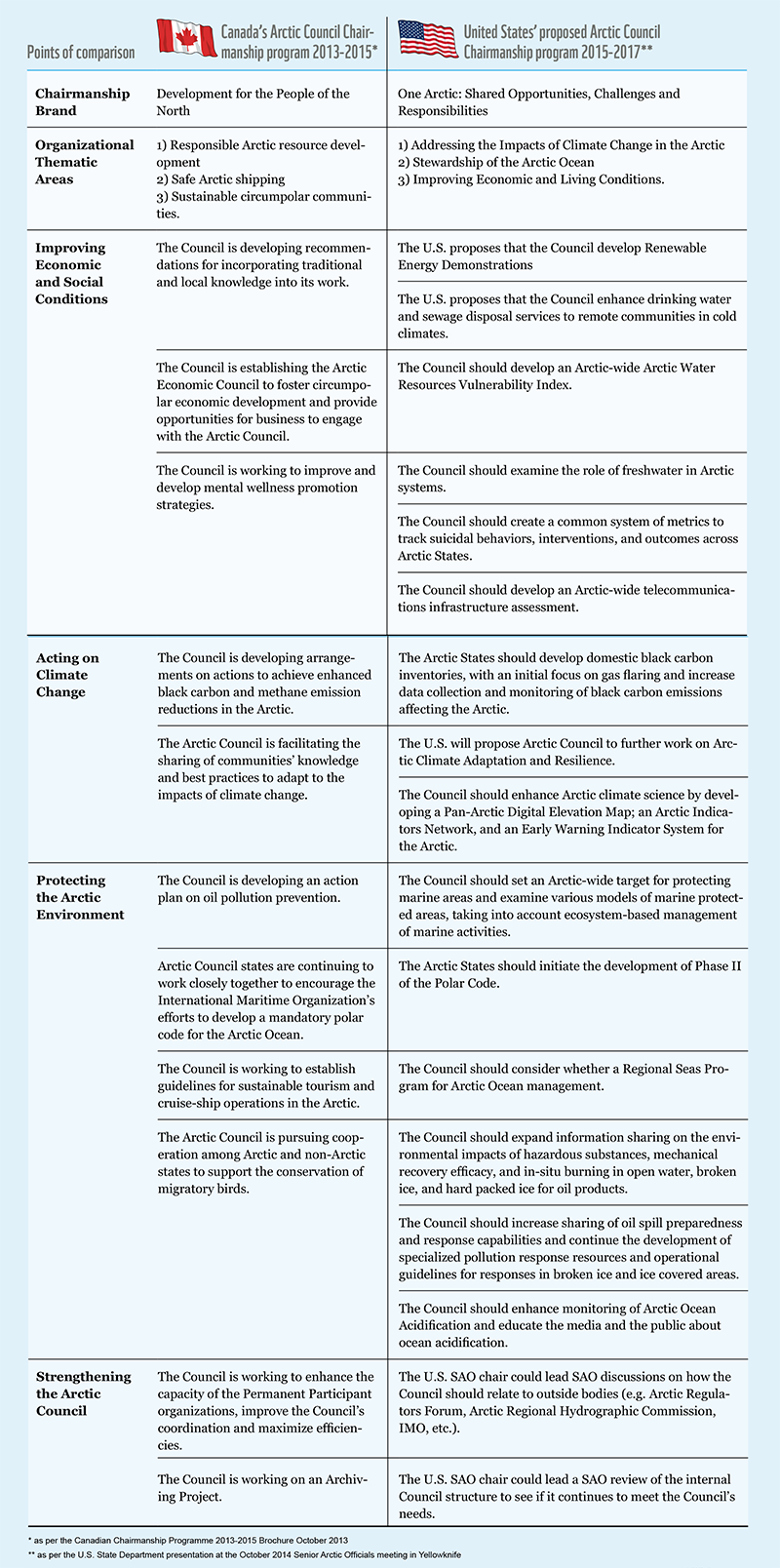

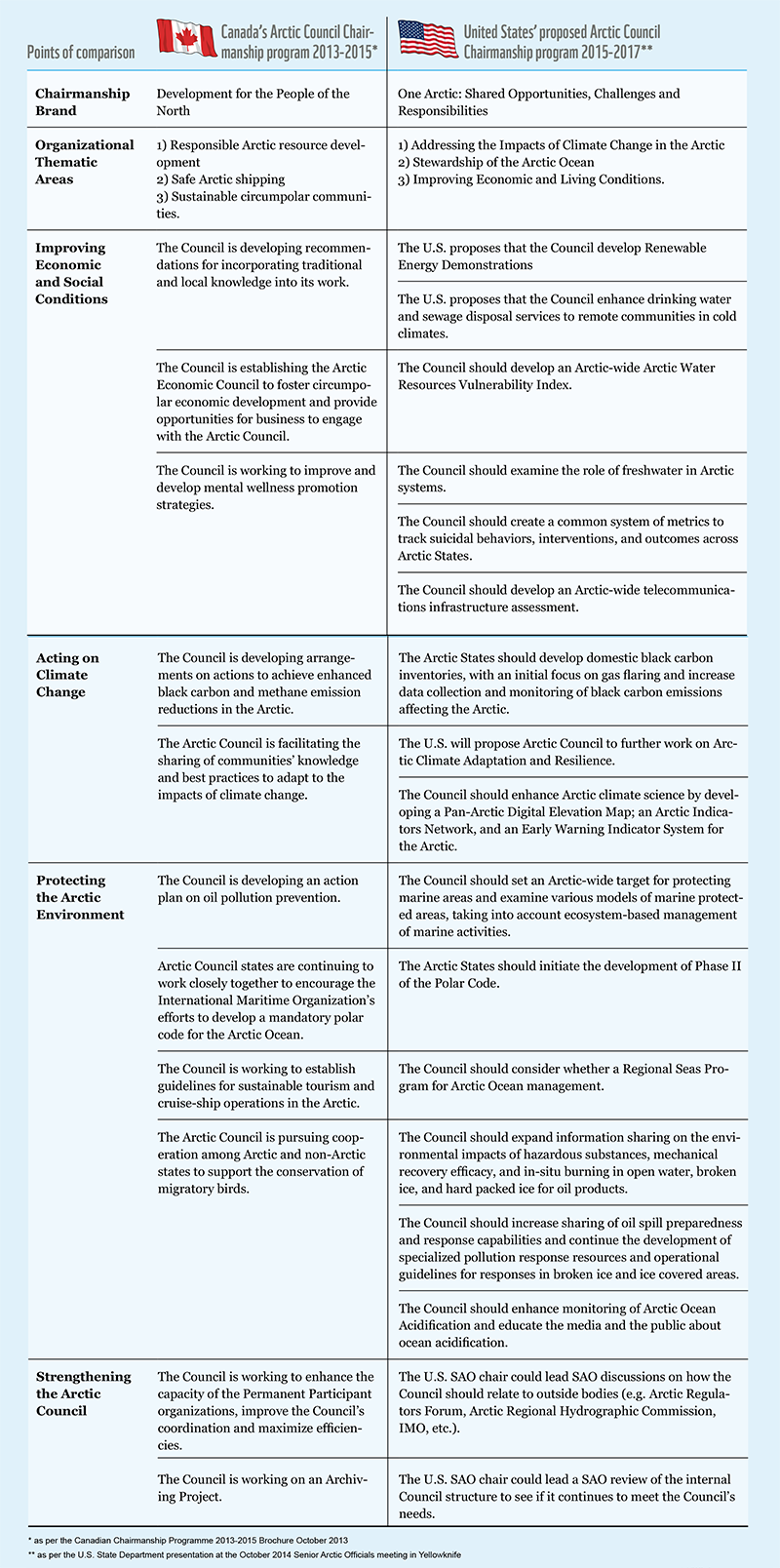

The United States has announced a thought-provoking and ambitious agenda for its term as Chair of the Arctic Council including initiatives on mitigation and adaptation to climate change, improving governance of the Arctic Ocean, and economic development within the region. It appears that coordinating national programmes and activities by the five Arctic Ocean littoral states is what is meant by improving governance in the Arctic Ocean. Whatever it proposes will take place in the context of proposals by all littoral states to extend their continental shelves into the Arctic Ocean according to processes detailed in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. Claims by these states to extended continental shelves overlap. It may be that during the American term as Chair of the Council, negotiation particularly with Russia outside this forum will take place among and between Arctic states to resolve competing claims.

Regarding climate—an issue not prioritized by Canada during its term as chair—the US may stress reduction in emissions of black carbon, a short-lived climate pollutant, both within the region and more broadly. The Council established a task force to look into this issue some years ago and an agreement to reduce emissions may well be announced at the April 2015 ministerial meeting in Iqaluit. The Arctic Athabaskan Council (AAC) has attended all meetings of this task force and repeatedly urged states to commit to reduce black carbon emissions. To date, Arctic states have addressed mitigation of climate change caused through emission of greenhouse gases—long-lived climate pollutants—globally through the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. A regional climate change mitigation agreement would signal a significant evolution of the Council and perhaps prompt other states to consider similar regional agreements. The US may soon have an opportunity to turn a paper agreement into on-the-ground reality.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, co-operation between the circumpolar states was new and untested. It was also confined primarily to scientific and environmental issues defined in the 1991 Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy in which Arctic Indigenous Peoples had only a limited role. Nearly 20 years later co-operation between the eight circumpolar states through the Arctic Council has become the natural order of things, and Arctic Indigenous Peoples intervene in debates and decision-making as Permanent Participants. AAC is committed to deepening and broadening circumpolar co-operation and informing global institutions about what the Arctic—the world’s barometer of climate change—is reading. Much depends on the political and diplomatic abilities of the United States during its term as chair of the Arctic Council to promote circumpolar co-operation at a time of changing and challenging geopolitics.

Gwich’in Council International

Put energy into energy

The Arctic is a magnificent but formidable place to call home. The winters are long, cold and dark and per capita energy use is almost twice the Canadian average. The Gwich’in people have survived and prospered in this climate due to a strong connection to the land and resourceful communities, however the cost of energy effects all Gwich’in people living in the remote north. These costs can be attributed to energy production, residential building science for the north and heating appliances. Gwich’in Council International would recommend the US Chairmanship explore each of these cost drivers and develop tools to assist communities in making decisions for addressing their unique energy needs during their tenure.

The majority of Gwich’in communities rely on diesel fuel for energy production. The diesel fuel for the most part is trucked in and in some cases flown in! The exploration of scalable renewable power generation technologies in the remote north would help to research sources of reliable, affordable and applicable alternative energy production in our communities to ensure continued prosperity of the people of the north.

Residential building science has improved to the point of Net-zero homes (homes that produce and consume equal amounts of energy). However, many homes built in the Gwich’in settlement area still use dated building practices and less efficient heating appliances. This combination yields poor insulation value, inadequate air tightness and inefficient use of resources for heat generation. GCI suggests a review of current housing inventories in the north and a comparative cost analysis of current residential building science vs. efficient building practices. The knowledge sharing of best building practices of States and Permanent Participants would be a tool to assist communities to make educated decisions for the future development and construction of homes in the north.

Gwich’in Council International looks forward to working on energy solutions with the United States Chairmanship in supporting the wellbeing and sustainability of the northern communities of the Gwich’in People.

The Saami Council

The Saami Council supports the concept of being one Arctic. We live in the Arctic together, even though the challenges might differ. The Saami Council, as one of the six Permanent Participants to the Arctic Council, is ready to share the responsibilities in the Arctic. As an Indigenous People in the Arctic, we do, however, face a reality that we are confronted with an uneven share of the challenges with the change in environment and not least with the change in land use. We have expectations that with the US lead, the Arctic Council and its member states will ensure and contribute so that the Indigenous Peoples in the Arctic also have equal access to the opportunities.

During the last decade there has been a lot of focus on climate changes and the Arctic Council is monitoring and addressing the impacts of these. With climate changes come also changes in the environment and changes in land use. To cope with these changes from a Saami perspective it is important to build robust and resilient communities in the high north. Socio-economic resilience is important for the communities to live through changes we still do not fully understand without lost identity and culture. This is the essence of sustainable development. The Saami Council therefore welcomes the conclusion of the Arctic Resilience Report during the US Chairmanship, as well as initiatives coming from the Adaptation Actions for a Changing Arctic (AACA) that will “produce information to assist local decision-makers and stakeholders…in developing adaptation tools and strategies to better deal with climate change and other pertinent environmental stressors”.

Saami Council looks forward to the US continuing the Canadian initiative to make better use of traditional knowledge and implementing actions to include TK in Arctic Council activities.