This article originally appeared in The Circle 02.15.

Despite its seemingly desolate landscape, the Arctic hosts an astounding diversity of species and habitats, and represents one of the most unique ecosystems on the planet. It is critically important to the biological, chemical and physical balance of the globe. Arctic biodiversity underpins planetary health and well-being, it contributes to the healthy functioning of the global ecosystem and is the foundation for many of the essential ecosystem functions and benefits on which we all depend. Dr. Braulio F. de Souza Dias says The Arctic Biodiversity Assessment, recently launched by Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF), the biodiversity working group of the Arctic Council, has made it very clear that Arctic biodiversity is being degraded.

Muskox, Devon Island. © Martin von Mirbach / WWF-Canon

Climate change is by far the most serious threat to Arctic biodiversity, exacerbating other threats such as ocean acidification, habitat degradation, pollution and, in some areas, unsustainable harvesting. The loss of biodiversity is expected to compromise the critical functions and benefits of Arctic ecosystems, with detrimental impacts on local livelihoods and lifestyles.

While climate change is the most significant driver of biodiversity loss, it is also expected to open up potentially significant economic opportunities in the Arctic, ranging from the opening of shipping routes to better accessibility of natural resources and decreasing costs for their extraction. We also know that the impacts of climate change on local livelihoods will not necessarily all be negative. Potential positive impacts might include higher summer salmon stocks, increased root and berry growth and larger whale populations. While net primary productivity may increase overall in the Arctic as a result of climate change, the effects of climate change on Indigenous peoples and local communities in the Arctic are very complex. Positive changes might cause further conflicts between traditional livelihoods and other land-use options. Managing change in the Arctic therefore requires full consideration of all environmental, socio-economic and cultural impacts, in particular on Indigenous peoples and local communities, as part of an ecosystem-based management approach.

The

Arctic Biodiversity Assessment recommends “mainstreaming” biodiversity – that is, the incorporation of biodiversity objectives and provisions into ongoing and future international standards, agreements, plans, operations and/or other tools specific to development in the Arctic. This would include economic activities such as oil and gas development, shipping, fishing, tourism and mining. This is well in line with the first goal of the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020, which calls for addressing the underlying causes of biodiversity loss.

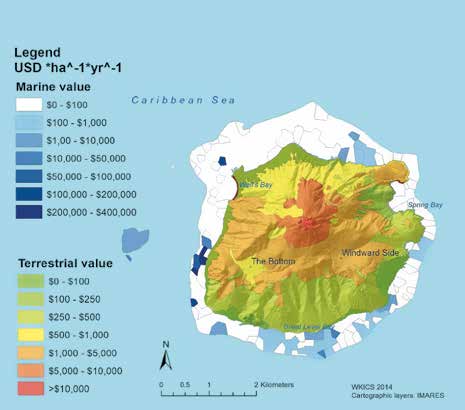

However, for such mainstreaming to be effective, the methodology and language for achieving mainstreaming needs to resonate with economic decision-making – that is, with economic decision makers, because ultimately all decisions are taken by individuals. While a simple comparison of costs cannot and should not be the sole basis for deciding whether or not a development project should be undertaken, monetary gains and profits are nonetheless regularly considered against environmental impacts.

How, then, to generate such resonance? It is here that the work of the TEEB initiative, with its TEEB Arctic Scoping Study, can play an important role and add further value to the

Arctic Biodiversity Assessment. Since its inception, one of the main objectives of the TEEB process has been to foster understanding between the economic and ecologic communities by integrating pertinent knowledge and methodologies in the evaluation of ecosystem services, using appropriate valuation methodologies, thus further operationalizing the concept of ecosystem services for human well-being that was developed and promoted under the 2005 Millennium Ecosystem Assessment.

When the global TEEB reports were launched in October 2010 at the tenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP) to the Convention on Biological Diversity, held in Nagoya, Japan, they generated significant interest. The reports were recognized as an important methodological tool for implementing the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020, and in particular Achi Biodiversity Target 2, which specifically calls for the integration of the manifold values of biodiversity, including economic values, into development and poverty reduction strategies and planning processes. In fact, the COP emphasized that increased knowledge of biodiversity and ecosystem services and the application of that knowledge are important tools for communicating and mainstreaming biodiversity, and invited the Parties to the Convention to make use of the TEEB study findings in order to make the case for investment for biodiversity and ecosystem services.

One of the stated goals of the TEEB initiative has been to examine the economic costs of biodiversity decline, and the costs and benefits associated with actions to reduce these losses. A basic premise of its work has been that valuation may be carried out in more or less explicit ways, depending on the situation at hand. Monetary valuation in particular is recognized as not always being necessary or appropriate – for example, when it is seen as contrary to cultural values or fails to reflect a plurality of values. At the same time, the open architecture of the TEEB approach provides interfaces with non-economic analysis and policy tools for effective interaction and synergy, such as the guidance adopted under the Convention related to Indigenous peoples and local communities. It is these features that make the TEEB approach so useful for the development of practical guidance for policymakers at the international, regional and local levels, in order to foster sustainable development and better conservation of ecosystems and biodiversity, including in the Arctic.

Dr. Braulio F. de Souza Dias is the executive secretary of the Convention on Biodiversity.