Many communities in the Arctic and its surrounding regions are located in remote places with harsh weather conditions. Yet experts agree renewable energy should be an integrated part of all development plans. PÁLL TÓMAS FINNSSON says renewables are already working in the Arctic, with a new push to integrate them with hydrogen. This article originally appeared in The Circle 03.15.

Two windmills in Iceland by the river Þjórsá.

© Jesús Rodríguez Fernández / Flickr / Creative Commons

ICELAND is in a privileged position when it comes to energy supply, with almost 100 per cent of its energy consumption deriving from emission-free renewable energy sources such as hydro- and geothermal energy. Despite the country’s abundant wind resource, wind energy has only recently been harvested here.

In 2013 Landsvirkjun, the national power company, started operation of two 900 kW wind turbines near the Búrfell hydro power station in southern Iceland. Both have been a great success, according to Margrét Arnardóttir, Project Manager for Wind Power at Landsvirkjun. “There have been very few operational disturbances and an absolute minimum of maintenance. The efficiency rate has exceeded all expectations and was 44 per cent in the first year of operation, which is well above the global average of 28 per cent.”

Despite the cold, snowy climate, the operational availability of the two turbines in 2014 was around 99 per cent and 97.5 per cent respectively. “The turbines operate with a storm control feature that allows them to generate electricity in winds of up to 34 metres per second,” Arnardóttir explains. “Moreover, they’re equipped with a de-icing system that blows hot air onto the blades when there’s risk of icing.”

Based on these initial results, Landsvirkjun is designing a 200 MW wind farm in Iceland, aiming to increase efficiency to over 50 per cent. Arnardottir has no doubts that renewable energy is a viable option in the Arctic. “Absolutely. Wind power is a relatively low-cost energy option and the environmental effect is minimal, provided it is carefully planned with respect for nature.” Solar energy is another renewable technology that has proven its worth in the cold climate of the north. In Piteå, Sweden, just 100 kilometres south of the Arctic Circle, a 20 kW solar panel test facility has produced impressive results.

“The system in Piteå gives the highest yield of all solar energy systems in northern Europe,” says Professor Tobias Boström of the Arctic University of Norway. “It produces 1500 kWh per year per installed kW of solar panels, which is really good.”

“It’s a tracking system that follows the sun,” he says. “It uses two different technologies, astronomical calculations that track the sun’s position and sensor technology that senses the brightest spot in the sky.”

And conversely, cold climate improves the yield and efficiency of the solar panels.

“When the temperature drops 20 degrees Celsius – for example from 10 degrees to minus 10 – and lower, efficiency increases by 10 per cent,” Boström explains. “The challenge is of course that the sun mostly shines in the summer and the further north you get, the less sun you have during winter. The issue of energy storage thus becomes more and more important the further north you get.”

Energy storage is a key issue in order to react efficiently to fluctuations in electricity production and ensure balance between supply and demand. This is complicated in isolated, off-grid communities with limited access to backup energy. These communities often rely on diesel generators as the only source of electricity, and in many cases, the fuel is delivered by helicopter.

Replacing these costly, fossil fuelbased systems with renewable technologies requires development of new energy storage solutions. Systems combining wind energy and hydrogen storage are currently being tested on the islands of Ramea, Newfoundland in Canada and in Stóra-Dímon in the Faroe Islands.

“The objective of these projects is to make the islands energy self-sufficient by utilising wind power and storing surplus energy as hydrogen. The hydrogen is then converted into electricity when there is no wind,” says Jón Björn Skúlason, Director of Icelandic New Energy. The demonstration projects will show whether it’s economically and technically feasible to start implementing such systems in remote communities in the north.

“This would release a vast potential,” says Skúlason. “Most of these communities have wind all year round, and in summer, there’s sunlight 24 hours a day. A robust, small-scale hydrogen storage solution would allow them to become fully self-sufficient with renewable energy.”

PÁLL TÓMAS FINNSSON is an Icelandic communications writer specialising in innovation, sustainability and Nordic culture.

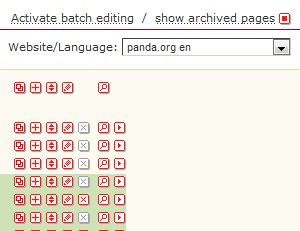

copy item

copy item add item

add item re-arrange items

re-arrange items edit item

edit item delete item

delete item preview item

preview item move item

move item ) – it means that you cannot perform that function – either because it is not permitted (For example – you may wish to delete a page which has live pages underneath and hence cannot be deleted directly), or because you do not have the required permission to perform that task.

) – it means that you cannot perform that function – either because it is not permitted (For example – you may wish to delete a page which has live pages underneath and hence cannot be deleted directly), or because you do not have the required permission to perform that task. Bold

Bold Italic

Italic Underline

Underline Strikethrough

Strikethrough Subscript

Subscript Superscript

Superscript Special Character

Special Character Numeric List

Numeric List Bullets List

Bullets List Internal Link

Internal Link External Link

External Link Remove Link

Remove Link Add Anchor

Add Anchor Place as Plain Text

Place as Plain Text View HTML Code

View HTML Code