This article originally appeared in The Circle 02.14.

The Arctic seas are under tremendous pressure from climate change and expanding human activity of unprecedented scale. JØRGEN SCHOU CHRISTIANSEN says our biological understanding of Arctic marine fishes is virtually absent, and strict precautionary actions are imperative. Christiansen is a professor of fish ecology at the Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway, and guest professor at Åbo Akademi University, Turku, Finland.

THE NEWLY RELEASED report on Arctic biodiversity presents the first comprehensive assessment of about 635 marine fish species across the Arctic Ocean and adjacent seas (AOAS). The most important outcome of this exercise is that we have finally structured our ignorance and identified some of our knowledge gaps. In short, our biological understanding of Arctic marine fishes is practically absent. Scientific uncertainty is difficult to broadcast and hard to sell, but it is nonetheless essential as it calls for strict precautionary approaches towards Arctic resources.

A few years ago, headlines in the media gave the misleading impression of Arctic fishes being overexploited. Subsistence fisheries along the Arctic coasts have been going on for centuries and the reconstructed catch records for a range of fishes such as whitefishes (Coregonidae) and salmonids (Salmonidae) accumulated to about 950 thousand tonnes in 57 years (1950-2006). This is absolutely minuscule compared with, for example, annual landings of more than 1 million tonnes from a single stock of herring (Clupea harengus) in the Northeast Atlantic. What is most disturbing, though, is the emerging full scale exploitation of petroleum and living resources in hitherto pristine parts of the Arctic seas.

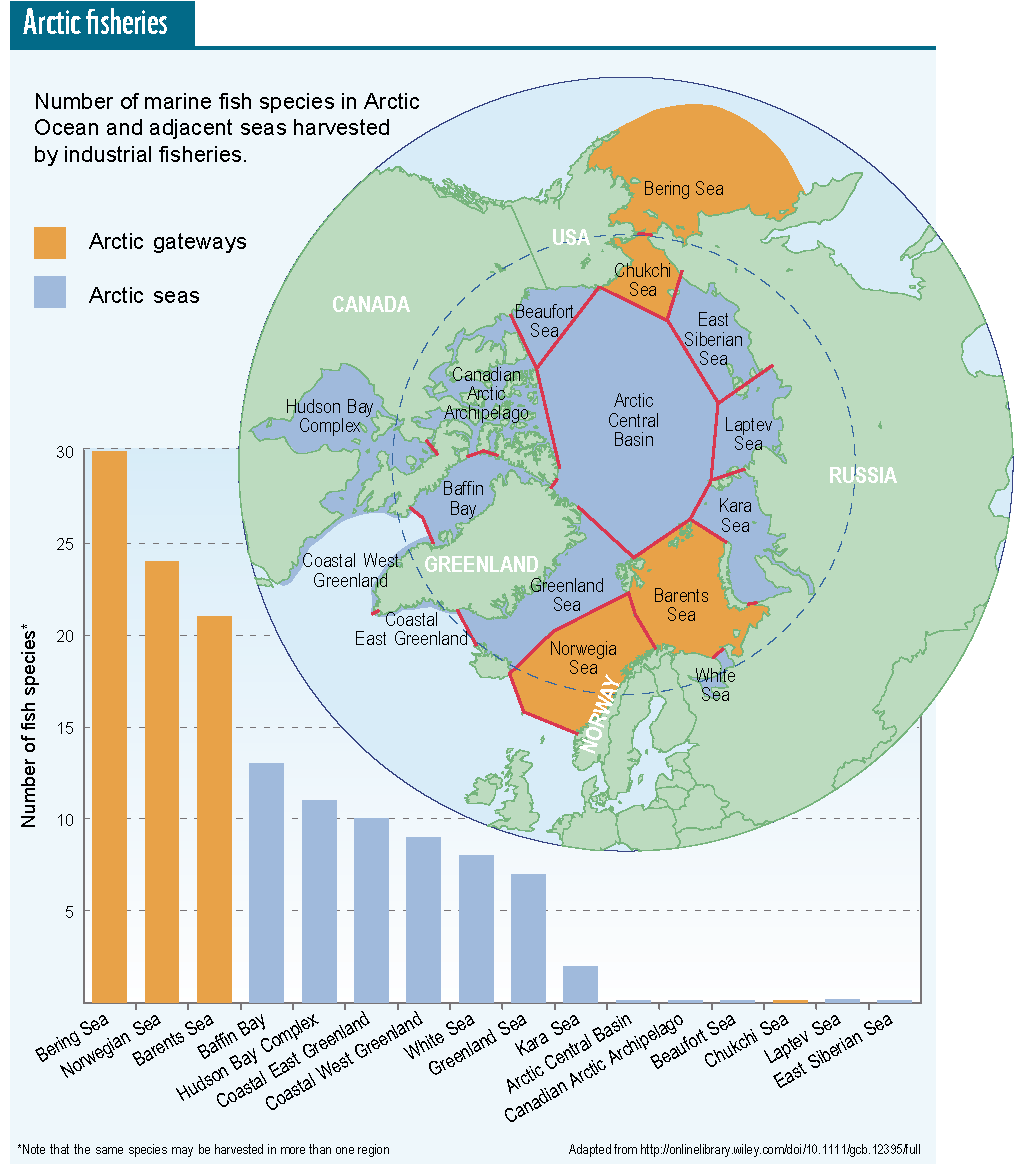

Among the 635 AOAS fishes, only 60 (fewer than 10%) are classified as being true Arctic. The remaining fishes belong to sub-arctic and southerly seas. The widely used phrase “Arctic fisheries” is false from a biological standpoint. Within the AOAS, industrial fisheries target about 60 species of which only three (5%) are Arctic: the codfishes polar cod (Boreogadus saida) and navaga (Eleginus nawaga), and the Arctic flounder (Liopsetta glacialis).

Databases covering the Arctic Ocean and adjacent seas hold a wealth of valuable information for the commercial species. But it is also a fact that data on non-target fishes are notoriously poor – bycatch species are either misidentified or lumped into categories of little biological meaning. This is particularly true for cartilaginous fishes such as sharks and skates, and species-rich fish families such as sculpins (Cottidae), snailfishes (Liparidae) and eelpouts (Zoarcidae). So, to keep up a precautionary view: better to be data deficient (“we haven’t got a clue!”) than misinformed (“our databases may show…”).

In light of ocean warming, targeted fishes spread rapidly into yet unfished parts of the arctic seas and marine toppredators, in the shape of industrial fishing fleets, obviously follow. For example, Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) is now common on the arctic shelves around Svalbard archipelago at latitude 80°N. Bottom trawls are by far the most used and most destructive gear in groundfish fisheries. The vast majority of Arctic fishes live at or near the bottom and do not migrate. Therefore, they are particularly vulnerable to conventional bottom trawling as they are lost to bycatch and destroyed seabeds. Although of no direct commercial value, bycatch species make arctic ecosystems work by feeding seabirds and marine mammals – wildlife that forms the livelihood of Arctic peoples. In contrast to the Southern Ocean, the Arctic is neither an outpost nor a frontier but homeland to Arctic peoples. They are the first to feel the pressures of climate change, big business and reckless actions from some environmental activists.

The detection of valid species and how they work in context of ecosystems is at the heart of biodiversity assessments based on scientific credibility and legitimate conservation and management actions based on societal values. Several Arctic fishes are controversial and difficult to identify and basic questions remain unanswered: how do fishes interact as prey and predator; how do they grow and reproduce; how old do they get and how do they cope with heat and pollutants?

We clearly need to integrate traditional/ community knowledge held by Arctic peoples and the natural sciences for legitimate conservation and management actions. This is indeed a huge, but not unsolvable, task. It must be based on mutual respect for the perception and rights of Arctic peoples to wildlife and habitat, and the methodological needs and rigor of science. Traditional ecological knowledge may provide valuable information to science on species distribution and abundance, shifts in biological events and changes in species occurrences and habitats. On the other hand, science may give useful advice on pollutant loads in wildlife and forecast potential consequences of climate change. Science needs traditional knowledge and traditional knowledge needs science. In the end, we all fall victim to failed conservation and management policies.

Read more on this in a recent Open Access paper in Global Change Biology.