Berta Tokeinna and son Jeffrey pick berries on the tundra, Serpentine river delta, Alaska, United States

© Global Warming Images / WWF-Canon

Nature, biodiversity, has a value. It has a value because we can enjoy a walk in the forest or the view of a birds’ cliff or just by being there. Indeed this value has been recognized by almost every country in the world, as witnessed by the very first lines of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity which state we are “Conscious of the intrinsic value of biological diversity and of the ecological, genetic, social, economic, scientific, educational, cultural, recreational and aesthetic values of biological diversity and its components”.

But in day-to-day decision making, nature is still often seen as a special interest for a few people who like rare species, rather than something that is of importance to all of us. This is where the concept of ecosystem services comes into play. Ecosystem services are the benefits that people receive from nature. Some of those benefits, such as food, firewood and timber, are obvious and are also regularly traded in markets. Others, such as flood control through forests or wetlands, or pollination of orchards by insects, can be less visible and are often taken for granted. That means they are usually overlooked when decisions are made that have an impact on nature, and we may suddenly find ourselves without the flood control we have always relied upon.

Ecosystem services are often divided into four categories:

- Supporting services are the basis for our survival on earth. They include photosynthesis, soil formation, nitrogen cycling, and they lay the foundation for the other ecosystem services.

- Regulating services can be the pollination and flood control of the previous example, but also local and global climate regulation by vegetation.

- Provisioning services provide us with products from nature for use as food, building materials, and fuel.

- Cultural services constitute a diverse category that includes our enjoyment of nature, inspiration or the benefits to our health.

By looking at nature through the concept of ecosystem services, the idea is that it will be easier to convince those who do not believe that they are interested in nature that nature should be of interest to them. In order to make this even clearer, it could be useful to actually put a value to those ecosystem services. In that case, benefits of a decision, for instance to build a new road, could be compared to its costs to ecosystem services. In some cases, it is not too difficult to valuate changes in ecosystem services; sometimes this can even be done in direct monetary terms, for instance changes in timber production when trees have to be cut to build a road. More often, however, it is much more difficult and in many cases we will have to be content just to know that these values exist, without exactly knowing how large they are.

Many people object to the concept of ecosystem services, and especially to the idea of putting a value (“a price”) on nature. They see it as too human-centred or disrespectful of nature’s own value. Traditional knowledge often takes a completely different view of life, and also many environmentalists think it is inappropriate to disregard the intrinsic value of nature in this way. Others see ecosystem services as the only way to make nature count in decision making.

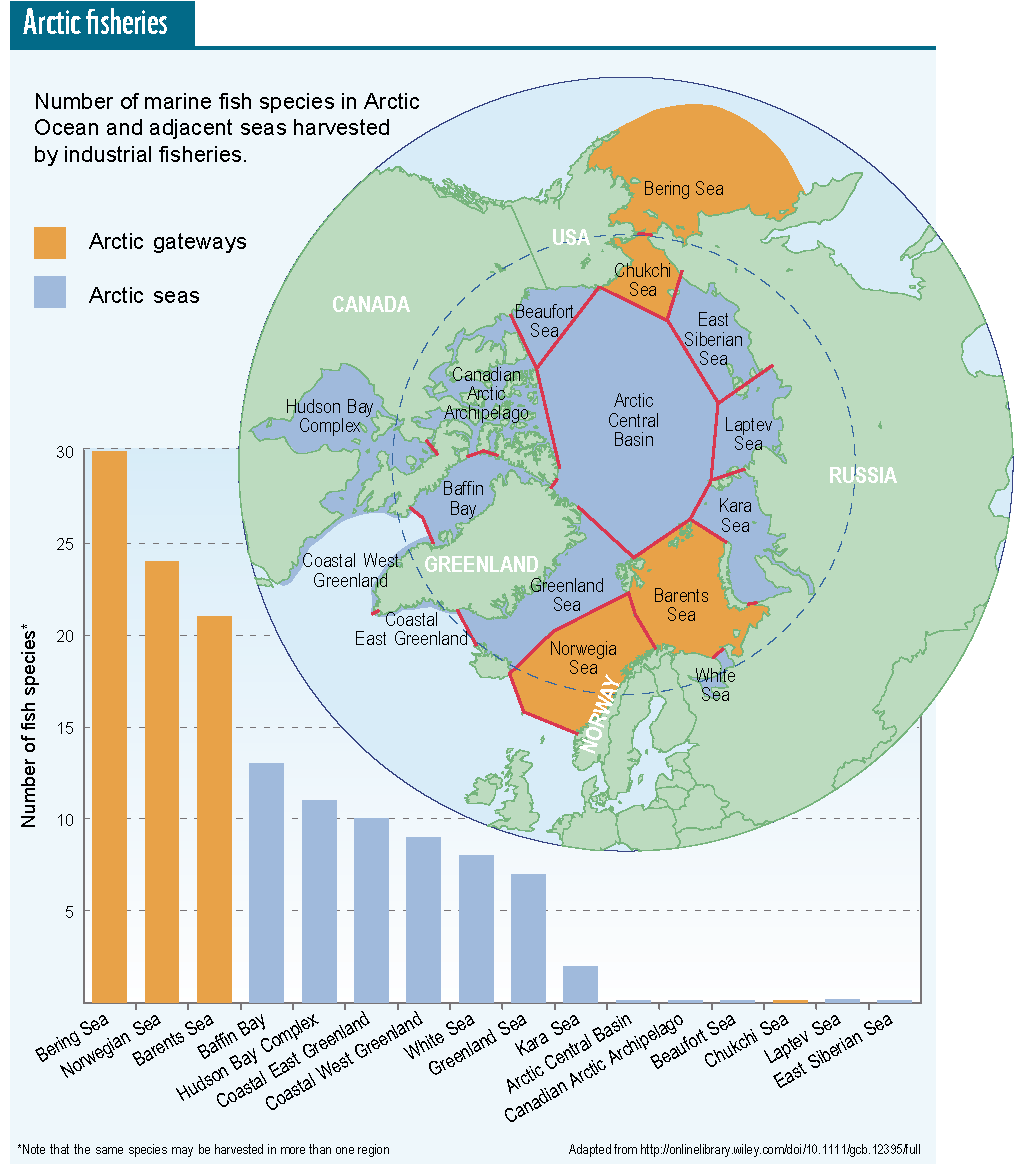

To date, the concept of ecosystem services has been studied to a limited extent in the Arctic, especially when compared with other regions of the earth. Studies of supporting and regulating services are largely absent. Providing and cultural services have been studied in more depth, and the chapter on ecosystem services in the Arctic Biodiversity Assessment describes examples of four provisioning services – reindeer herding; commercial fisheries; commercial and subsistence hunting, gathering and small-scale fishing; and recreational and sport hunting – and two cultural services – tourism and non-market values. Since so much of the work on ecosystem services has been done in very different environments, ongoing studies, led by WWF, on how and where an assessment of the ecosystem services provided by Arctic biodiversity can take place will be of great importance.

How do you put a value on Arctic biodiversity? Let us know what you value with this survey by July 15, 2014.

This article was originally featured in The Circle 02.14.